Exploring Moscato

Sometimes a fun, fresh, informal, tasty wine is exactly what the moment calls for.

I am presently visiting family in sunny California, and have found myself turning to Moscato for refreshment while tending the grill and chillaxing. So, I thought I’d revisit the Bartenura Moscato d’Asti aka the “blue bottle” and, more generally, explore the joys of Moscato.

NOTE:

As Italian wine can be complex at times, even though Moscato is not an especially complicated wine, I’ve tried to keep the harder-core wine-geek content to “notes” such as this—readers who find this sort of detail boring can skip these without missing a beat.

Also, I’m finding that when not constrained by editorial deadlines and space considerations, I tend to write without too much concern for length—if folks prefer that I cut future blog posts short, just let me know.

The Muscat Grape

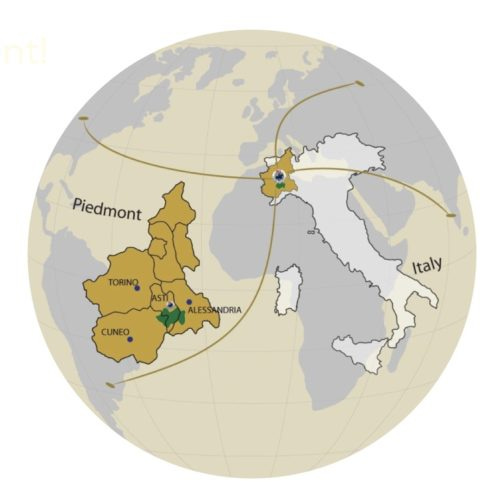

Moscato, or more properly for my purposes here Moscato Bianco (white Muscat)—or even Moscato di Canelli, named for Città di Canelli, an Italian town in Piemonte (generally rendered as Piedmont in English), where the grape has been cultivated for many hundreds of years and, for the pedants and purists among us, is known in France as Muscat Blanc à Petits Grains—is just one variant of the Muscat family of grapes.

Thought to have originated in Greece, from whence it spread across the Mediterranean basin and beyond, the name Muscat comes from the Greek word μοσχάτο (mos’-khos; it is the noun form of the neuter adjective for “musky,” though in a nice sense). The various related Muscat grape cultivars also all share some basic similarity of name, as they are all ultimately based on the Greek name (though there are also some unrelated variants that acquired a related name over time—DNA analysis has helped researchers sort through it all).

Cultivated all over the world, the Muscat grape has an ancient history, and a massive family. The British wine writer Oz Clarke summed it up nicely in his book Grapes & Wines,

If there is a more complicated family of grapes than the Muscats, it has yet to be discovered. There are over 200 vines in the world called Muscat Something-or-Other, and some are related, some not. Muscat Blanc à Petits Grains, Muscat of Alexandria and Muscat Hamburg – the three best-known Muscats – are related, and their capacity for mutation can make the Pinot family look positively regimented. Their berries can be golden, pink or black, and Muscat Blanc à Petits Grains is notorious for its ability to produce one colour one year and another the next. If they were human the Muscat family would be regarded as hopelessly feckless. Which just goes to show that orderliness is not everything.

One of the Muscat family’s chief attributes—apparently across all the related varieties (for this I must rely on the reference books as I’ve only personally encountered but so many of them)—is the grape’s distinctive pungent and grapey aromatic and flavor characteristics, which have led some towards adoration. As wine writer Karen MacNeil observed in the 2nd edition of her wonderful Wine Bible,

No matter what anyone says, I doubt Eve was tempted by an apple in the Garden of Eden. A cataclysm of original sin . . . all for a plain apple? It makes no sense. Some muscat grapes, on the other hand, could have done it. Intensely aromatic and awesomely delicious, muscat is irresistible. If every luscious, ripe fruit in the world were compressed into one phantasmagoric flavor, it would come close to evoking muscat.

[DIGRESSION:

Ms. MacNeil is possibly on to something here! The Talmud (Berachot 40a; also quoted without the Torah citation in Sanhedrin 70a-70b), records a beraita [ברייתא, Aramaic for "outside material,” referring to a body of oft quoted teachings formulated by Mishnaic era sages but that was not included in the Mishna] that also argues in favor of the wine grape over an apple as the forbidden fruit in the Garden of Eden: “Rabbi Meir says: The tree from which Adam the first man ate was a grapevine, as since the thing that most causes wailing to a man is wine, as it is stated with regard to Noah: “And he drank from the wine and became drunk.” The Talmud is obviously making a very different point than MacNeil, but still…]

The Nobility of White Muscat

The Moscato Bianco variant is arguably the most important variety of Muscat and is thought to be very possibly the progenitor of the Muscat family of grapes. Jancis Robinson, MW, heralded this variety as, the “most noble sort of Muscat,” noting that it is one of the very oldest known grape varieties, familiar to the ancient civilizations of both Greece and Rome—“its history is many times longer than that of such newcomers as Cabernet Sauvignon.”

Ms. Robinson also noted that, “[t]his sort of Muscat is capable of producing wines with real finesse and a particularly pure, floral sort of grapiness.” Indeed, nearly all Muscat grapes are unique amongst wine grapes in that they generally produce wine that actually smells and tastes of the grapes they are made from. One can generally sense in the glass some of the same grape aromas found in the vineyard. Many even consider Moscato Bianco as good for eating as for winemaking.

Since this “most noble” variety of Muscat grape is grown all over the world, Moscato wines can be produced anywhere that wishes to do so, and in keeping with this viticultural diversity, are produced in any number of styles, from dry to cloyingly sweet, and from still to sparkling, and even fortified. There are also a reasonably wide variety of kosher Moscato wines on the market.

NOTES:

There are some enjoyable kosher wines made from other Muscat varieties too. See, for example, the lovely Anna from the Dalton Winery in Israel based on the Muscat of Alexandria variety; or the Zion Estate Muscat Hamburg also from Israel; or the generally yummy Otto range of wines from House of Hafner in Austria based on the Muskat-Ottonel (two of these are also available here); or the tasty Herzog Late Harvest Orange Muscat, a cross between the noble sort of Muscat and the Chasselas grape; or the Jeunesse Black Muscat also from Herzog Wine cellars in California.

My CA winemaker friend Craig Winchell, formerly of the Agua Dulce Winery and before that of the now legendary Gan Eden Winery, was the first to produce a kosher late harvest style Black Muscat in 1992, with additional vintages released ‘93, ‘94, ’96, and then again in 1998. He had also released a wonderful rosé version labeled as Moscato Nero in 1995.

On the theme of global Muscat cultivation, there is a group called the Forum Oenologie Association which holds an annual “Muscats du Monde” festival in late June/July in the city of Frontignan-la-Peyrade, in the Languedoc-Roussillon area of France, presenting awards for the world’s best Muscat wines.

The Moscato wines of Asti

Italy has enjoyed an especially long, deep and rewarding history with Moscato. That wine-soaked nation undertakes an agricultural census every 10 years, the most recently available of which is 2010 (the next one commenced only in 2021 but should be released sometime this year). The 2010 census identified eight different Moscatos cultivated in Italy, but the most prominent is far and away the Moscato Bianco. As wine writer Ian D’Agata notes in his 2019 book Italy's Native Wine Grape Terroirs,

Moscato Bianco owns the distinction of being the only grape variety to be grown in every region of Italy. This cannot surprise anyone given that it makes some of the country’s most-loved wines, like Asti and Moscato d’Asti.

According to the more up to date growing data of Italian Wine Central (IWC), total plantings of Moscato Bianco are 13,538 ha (33,439 acres) and Moscato is counted as a “majority component in one or more” wines of 34 different DOCs, which also means it is officially one of Italy’s most planted white wine grapes. Per IWC figures, Piemonte accounts for 79% of all plantings, with the Asti DOCG region obviously being the “best known.”

The DOCG designation is part of Italy’s appellation system—Denominazione d’Origine Controllata e Garantita means “controlled and guaranteed designation of origin,” and basically certifies that the wines bearing the DOCG label come from a delineated location, made using traditional grapes, and by approved methods of production.

LONG WINE-GEEK SIDENOTE ON ITALIAN MOSCATO GRAPE STATS:

The generally excellent Oxford Companion to Wine seems to have gotten this detail wrong, for it states: “The Italian vine census of 2010 identifies seven different Moscatos.” When I checked the census directly and then the National Registry, however, I came up with eight different Moscatos, not seven, though admittedly I was confused by some possible repetition. So I reached out to the good folks at Italian Wine Central (IWC), one of the better online resources, and was told, via email, by Jack Brostrum that I was “correct and the Oxford Companion is wrong” though exactly what is meant by “‘types of Moscato’ might open the door to some debate.”

He noted, for example, that “Moscato di Alessandria is also listed in the census, but only by its more common Italian name Zibibbo (it also appears twice and I don’t know why),” and so also is “another relative, Moscatello Selvatico.” Meanwhile,

Moscato di Terracina is apparently unrelated to other Moscatos and so might not be considered a ‘type of Moscato,’ and the same might apply to Manzoni Moscato, which is a crossing of Raboso and Moscato d’Amburgo (Muscat of Hamburg)—the latter of which doesn’t appear on the census because it wasn’t entered in the national registry of vines at the time.

For Brostrum, this is all part of the “endlessly entertaining game of making sense out of Italian wine statistics.” Just so.

Fortunately, Mr. Brostrum also helpfully pointed out my next step. “The best source on this subject,” he wrote, “is Ian d’Agata’s book Native Wine Grapes of Italy, but as you can see, there is rarely a definitive answer to a question about Italian wine.” I had recently finished reading Mr. d’Agata’s excellent 2019 book Italy's Native Wine Grape Terroirs, and already had his earlier 2014 Native Wine Grapes of Italy on my to-read pile. This pushed it to the top of the pile.

Thankfully, Mr. d’Agata’s 2014 work clinches it:

Today, Italy grows at least eight different Moscato varieties (at least, eight are officially recognized in the National Registry thus far), the most abundant of which is Moscato Bianco. Wine lovers would do well to become acquainted with this family of grapes, as some of their wines are among Italy’s most interesting, and greatest.

Indeed.

LONG WINE-GEEK NOTE ON ITALIAN WINE QUALITY CLASSIFICATIONS:

When Italy became part of the foundation of the European Economic Community (EEC), it sought ways to conform—the treaty was signed in 1957, but the EEC was officially founded in 1958. By 1963, Italy established its version of the French Appellation d'origine contrôlée (AOC) system of laws. According to both Italian and European Union law, every winegrowing area in Italy is assigned a quality level based on a variety of factors including, in part, the area’s viticultural and winemaking standards, perceived prestige, and historical significance. The pattern is a basic quality pyramid.

In principle, the highest quality level in Italy—the top of the pyramid—is Denominazione d’Origine Controllata e Garantita or DOCG. The second quality level is Denominazione d’Origine Controllata or DOC (“controlled designation of origin”). EU laws change, however, and currently the EU officially considers both the DOCG and the DOC to be at the same level of the EU’s Protected Designation of Origin or PDO—which is known in Italy as Denominazione d’Origine Protetta or DOP (it just means “Protected Designation of Origin”)—though the EU rather charitably allows Italian producers to continue to use both the DOCG and the DOC terms. Isn’t that nice?

The third quality level, below the DOC (or the DOP), is known as Indicazione Geografica Protetta or IGP (“Protected Geographical Indication”), the requirements of which are significantly less stringent or rigorous. This same quality level used to be called IGT for Indicazione Geografica Tipica (“indication of geographical typicality”), and producers are allowed to use either term—IGP or IGT—on the label.

The bottom of the quality pyramid, the fourth level, is known simply as Vino, it used to be known as Vino da Tavola or VdT (“table wine”) and simply means that the wine is made of grapes and comes from Italy.

The Moscato Wines of Asti continued

The Moscato Bianco grape has been cultivated around the Piemonte region of northwestern Italy for many centuries. Piemonte means “at the foot of the mountains” and borders Switzerland in the north and France in the west, essentially hemmed in by the Apennines in the south and the Alps in the north. As of 2020, per IWC figures, the region had 43,872 ha (108,400 acres) of vineyards registered, with Moscato making up 22% of all plantings.

Specifically in the Asti production zone of Piemonte, the first known reference to the Moscato Bianco grape is from the early 13th century in the records of the town of Canelli. The “Consorzio per la Tutela dell’Asti” (“Consortium for the Protection of Asti”) was founded in 1932—two years before Barolo saw its version—to protect, develop and promote Asti and Moscato d’Asti wines worldwide. The Consorzio’s trademark is Saint Secundus, the patron saint of Asti, on horseback. Asti was officially granted DOC status in 1967 and was later elevated to DOCG status in 1993.

In early 2012 the Asti Consorzio was given formal responsibility by the Italian Ministry of Agricultural, Food and Forestry Policies for maintaining the quality control of the DOCG wines of Asti and for promotion of the appellation. A major long-term viticultural sustainability and quality upgrade campaign was launched in 2015, so at least in theory overall quality should be improving in the near term.

In Asti the Moscato Bianco grape is most famous for two styles of wine: Moscato d’Asti DOCG and Asti DOCG. [There is also a separate small but well regarded category of Moscato d’Asti known as Vendemmia Tardiva or Late-Harvest.]

Making Asti DOCG and Moscato d’Asti DOCG

Asti wine, which used to be known as Asti Spumante (Spumante means foaming), is a fully sparkling wine, made very occasionally in the Metodo Classico (the “classic” method of Champagne), in which a second fermentation takes place inside the bottle, but most usually and most typically is made in the much cheaper Asti version of Metodo Martinotti, sometimes described as the Asti process, in which the first and only fermentation is done in bulk in refrigerated tanks, and the yeast is simply filtered out once the desired level of development is achieved. Asti wine producers will actually produce wines throughout the year, keeping the must near freezing until the next batch is needed—every two-months or so.

Once the wine comes to the desired level of sweetness, they filter out the yeast cells to prevent the fermentation continuing further. The result is fully sparkling, and usually with an alcoholic strength akin to a strong beer, 6-9.5%, though the limits on alcoholic strength were removed in 2020; likewise, Asti can now be produced at any desired sweetness/dryness level. The atmospheric pressure in Asti is high enough that it requires, Champagne-like, a heavier bottle with thick glass, and a Champagne-style cork with a protective wire cage.

Moscato d’Asti is made in essentially the same way, except that the quality of grapes used for production is typically much higher, the length of fermentation is shorter, the alcohol level is lighter, the natural sweetness level is higher, and the atmospheric pressure is necessarily less, so the bubbles are gentler—what the Italians call frizzante or fizzy. Initially the fermentation is done in open tanks, allowing the carbon dioxide to release (as is normal with all still wines), but once the desired style is reached but before the fermentation is finished, the tanks are sealed, forcing the carbon dioxide back into the wine. Then it proceeds apace—fermentation is chilled to a stop, the wine is filtered, and bottled in normal bottles, with normal corks.

Generally, Moscato d’Asti gets the ripest and healthiest grapes in service of the style’s delicate floral yet distinctly musky style, while the less ripe grapes will typically be used for Asti (or vermouth). Under the DOCG regulations, Moscato d’Asti cannot exceed 2.5 atmospheres of pressure, its minimum level of alcohol by volume is 4.5%, with a maximum of 6.5%.

NOTE:

In Italy, this tank method of fermentation is named for Federico Martinotti who, in 1895, invented and patented a refermentation method using large tanks; he was the director of what is now the Istituto Sperimentale per l'Enologia (Experimental Institute for Oenology) in Asti. The problem he focused on was how to clear sediment from finished wine, using the existing available technology for measuring sugar in wine that had been developed in Champagne by André François, coupled with the then still new and exciting discoveries of Louis Pasteur regarding fermentation as the work of yeast on sugar. The missing part of the equation was stainless-steel, allowing for the development of equipment that would actually work well.

Around 1907, Eugène Charmat, an agricultural engineer at the Université de Montpellier in south-east France, was able to use early versions of what became stainless-steel to put the method into practice. Mostly the focus is on a second fermentation of a base wine, as is done in Champagne, rather than one fermentation as in Asti. Outside of Italy, this method is typically named for Charmat if any name is appended to it—though usually it is simply called some variation of “tank method”.

The taste of Moscato

Moscato typically has very distinctive aromas and flavors. The popular Wine Folly website suggests that readers should, “[e]xpect sweet aromas of peaches, fresh grapes, orange blossoms, and crisp Meyer lemons” noting that “[t]he flavor tingles on your tongue from acidity and light carbonation,” giving “the perception that Moscato d’Asti is just lightly sweet.”

Meanwhile, wine writer Ian D’Agata writes in his 2019 book Italy's Native Wine Grape Terroirs, “a good Moscato d’Asti always reminds me of orange blossoms, grapefruit, pear, sage, rosemary, and vanilla...and good examples are always long on flavor and short on alcohol.”

To my mind, both descriptions cover the range nicely, though I’d add ripe nectarines, apricots, lime, wisteria, honeysuckle, and, of course, that distinctive musky perfume of the aromatic white muscat grape.

Moscato’s unique perfume stems from terpene molecules, and of the more than 20 aromatic compounds involved, the most significant is said to be linalool, which is often associated with aromas and flavors like apple, honey, pineapple, sage, lavender, rosemary, bergamot, basil, and lime, among others. It is linalool which imparts that impression of sweet muskiness.

In the growing season in Asti, linalool begins to appear around the start of August, and then dissipates, adding yet another consideration to the decision-making process regarding when best to harvest—this is on top of such factors as grape ripeness and levels of acidity. Once the final wine is bottled, linalool concentrations drop significantly inside of around three years, which is a large part of why Moscato wines are best consumed on the young side.

Of course, taste, like personal sensory receptivity generally, is subjective and necessarily individuated, so mileage will vary greatly in terms of picking out this or that scent or flavor from the glass in hand. That said, wines based on highly aromatic grapes, like the Muscat family, generally lend themselves to relatively effortless discernment.

Given the many laudable attributes of Moscato it should come as no surprise that Moscato d’Asti wines, and other Moscato based wines made in the same style, should have become so popular over the last decade.

Moscato got popular, suddenly

Back in 2006, the wine writer Matt Kramer, in his great if now dated book Making Sense of Italian Wine, wrote,

There really aren’t any bad Moscato d’Asti wines on the market. Unlike Asti Spumante, it’s still an artisanal item and market demand is not (yet) so great as to invite the wine industrialists into the picture. Of course, there are better and worse versions, but they’re all pretty good.

I’m not sure Kramer’s observation— “an artisanal item” untouched by “wine industrialists”—was still entirely accurate by the time his book was published, but certainly things undeniably changed by the early 2010s. Indeed, Moscato d’Asti saw astronomic growth in demand in the United States in the last decade; and not just the original Moscato d’Asti, but indeed any form of Moscato made in that style. Esteemed wine culture magazines like the Wine Spectator, among others, began referring to this new popularity as “Moscato Mania,” and the like

By 2012, the Nielsen Company, an American “information, data and market measurement firm,” reported that 2010 saw a 100% jump in sales with 2011 seeing a 73% jump on top of that, which of course led winegrowers in California and elsewhere to invest in more Moscato plantings. While demand for Moscato in the US eventually slowed, the category continues to grow.

Some folks attributed this sudden growth to hip-hop artists embracing and singing about Moscato, starting with Lil’ Kim’s 2005 song Lighters Up from the album The Naked Truth (“Still over in Brazil sippin' Moscato/ya must have forgot though/so I'mma take you back to the block yo/put you on to how we rock yo”.)

There wasn’t an awful lot of Moscato d’Asti on the market in the US at that time, however, but the good folks at the Herzog family’s Royal Wine Corp., the largest producer, importer, and exporter of kosher wine in the United States and Europe, had already established an easy to recognize kosher brand in a distinctive blue bottle, and decided to embrace the moment with a massive marketing push. The rapper Drake then drove the Moscato craze further in 2009, and other rap artists soon jumped on the bandwagon. Bartenura quickly became an easily recognizable brand of choice. DJ Khaled, for instance, released a music video called I'm On One with explicit Bartenura product placement to go along with the explicit lyrics. Even the Real Housewives of Atlanta got in on it.

Indeed, by 2017, it wasn’t so bizarre to see the hip-hop artist Lil Wayne explicitly promote the Bartenura brand, posting a photo on Facebook of the bottle with the caption, “Fellas Valentine’s Day is coming up. Have a glass of Bartenura Moscato with your lady and thank me later!”

Bartenura was suddenly mainstreamed into the non-kosher wine market and catapulted to the front of the pack. In 2012, for instance, the wine industry news-wire Shanken News Daily reported:

New Jersey-based Royal Wine Corp. has a hit on its hands with Impact “Hot Prospect” Bartenura, a premium Italian label that has nearly doubled in volume since 2008, depleting 247,000 cases in 2011, according to Impact Databank. This year, Royal Wine CEO David Herzog says Bartenura will likely reach 400,000 cases on a volume increase of 60%. [Note: At 12 bottles per case, that is 4,800,000 bottles.]

By 2017, Shanken News Daily reported that,

Bartenura, known for its Italian Moscatos, has roughly doubled in size in the U.S. since 2011, according to Impact Databank, and is poised to cross a half-million cases this year.

The Bartenura Moscato Blue Bottle Brand

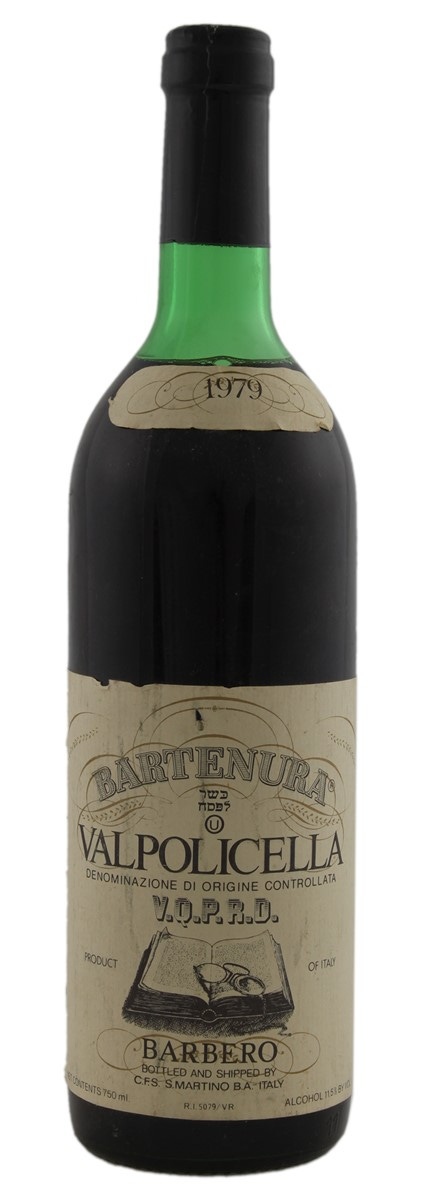

The Bartenura brand of kosher Italian wine was first launched in 1978 by the Royal Wine Corp. The idea, spearheaded by the then CEO David Herzog (his son Mordy is the current CEO), was to introduce to the American market dry kosher table wines that were on par with the popular non-kosher table wines of that period — so Italy’s famously food-friendly wines were a natural starting point.

“Our first dry kosher imports,” as Nathan Herzog, Royal’s current president (and David’s nephew), once told me, “were the 1978 Bartenura Valpolicella and the Bartenura Soave.”

These imports were part of a long-term mission by the Royal Wine Corp—and since then the mission has been embraced by much of the rest of the kosher table wine industry as it began to form and take shape—to smash the negative image of kosher wine as sickly sweet sacramental wine.

The brand was named for Rabbi Ovadiah ben Avraham of Bertinoro [עובדיה בן אברהם מברטנורא], a 15th-century Italian rabbi and famous commentator on the Mishnah, conventionally known as simply “The Bartenura.” The name was thought easy to recall and familiar to its target audience.

Royal’s Bartenura line sold well, the portfolio was expanded, and kosher competitors emerged. One of the portfolio extensions was a sweet wine, the sparkling Bartenura Asti Spumante (in keeping with mainstream tastes of that period). Royal partnered with the Italian winery Gruppo Araldica Castelvero to produce this brand in 1981.

One of the competing brands of kosher Italian wine produced for the American market was “Rashi,” named after the 11th-century French biblical commentator Rabbi Shlomo Itzchaki (1040-1105; best known by the Hebrew acronym of his name [רש"י]). Recognizing a good thing, Royal acquired the Rashi brand in the late-1980s, and it was under the Rashi label that kosher Moscato d’Asti first hit the U.S. market with “just a few thousand cases a year,” according to Herzog.

Starting with the 1991 vintage, Royal began selling a Moscato under its Bartenura brand too. As wine writer Adam Montefiore observed, “Its sweetness, low alcohol and easy drinking nature would surely appeal to the Jewish consumer, who was still wedded to sweet wines.”

Then in 1993, Royal decided to change the packaging from the traditional, green-tinted bottle to the now internationally recognized, and much copied, “blue bottle.”

Moscato d’Asti had just been elevated to DOCG status in 1993, however, and Italian wine regulators began complaining about Bartenura’s revamped packaging. Claudio Manera, the then managing director and now CEO of Gruppo Araldica, recently told me the blue glass was problematic because “at the beginning DOCG appellation” would “allow only [the] traditional green glass.” Eventually, “after [a] long time chasing the DOCG Consortium accepted our request”—but it took years.

The regulatory issues dogged the brand for some time, explained Gabriel Geller, Director of Public Relations and Advertising and Manager of Wine Education at Royal. Royal was forced at one point to switch production to the province of Pavia, in the Lombardia (Lombardy) region of northern Italy. The packaging remained, and nobody seemed too put out by the sudden switch from Moscato d’Asti to Moscato Provincia di Pavia IGT. As Geller put it, the Bartenura Moscato “went back and forth from Pavia to Asti” due to these “regulations issues” but eventually the Moscato d’Asti DOCG relented, and the brand “is firmly Asti [DOCG] again.”

“We nearly killed the blue bottle,” Jay Buchsbaum, Royal’s Executive V.P. of Marketing, told me some years ago. “We had supply and cost-control issues and a regulatory headache in terms of the bottle’s blue hue,” he said. “Those who wanted to simply switch back to the easier and cheaper green [bottle] had a strong case,” he recalled, “but thankfully we stuck with the blue.”

Obviously, that decision worked very well for the Royal Wine Corporation. Today, according to figures supplied by Geller and by Manera, annual production of the Bartenura Moscato d’Asti is about 1-million cases, or 12-million bottles, plus 2.5 million cans (which they introduced in 2020; though the cans are from Pavia — DOCG regs again). The brand is also now exported to 38 different countries.

To put this in perspective, based on figures from Geller, the second best-selling kosher wine in the United States “is likely the [Herzog Wine Cellars’] Jeunesse Cab”, a semi-sweet/semi-dry red wine which has annual sales of around 60,000 cases, or 720,000 bottles.

NOTE:

As the Bartenura brand has been growing over the last four decades, Gruppo Araldica, where many of the Bartenura wines are actually produced, has grown in tandem. “The volume of kosher wines is now so large,” Herzog told me back in 2018, “that a part of their [then] greatly expanded and [then] updated winery [Araldica Vini Piemontesi in Castel Boglione] “has been sectioned off as kosher year-round.” According to Claudio Manera, Gruppo Araldica’s CEO, a full 40% of their production is kosher at this point.

The Joys of Moscato

At their best, the Moscato d’Asti wines are deeply perfumed, balanced, sweet but not too sweet, fetching, and indeed refreshing— “flirtatious liquids” is how Jancis Robinson described them—and they make for popular drinking with or as dessert, or to brighten up one’s afternoon, or to refresh after mealtime.

In the current edition of the Oxford Companion to Wine, Walter Speller, observes:

Moscato d’Asti is not a classic dessert wine, its chief virtues being its delicacy, its intense aromas, and a sweetness that is as much suggested as forthrightly declared. While Moscato d’Asti’s reputation as ‘the perfect breakfast wine’ contains a nugget of truth…

Similarly, in the 8th edition of their always masterful World Atlas of Wine, Hugh Johnson, OBE, and Jancis Robinson, MW, refer to Moscato d’Asti as “distinctly superior” over Asti, and “the epitome of sweet Muscat grapes in its most celebratory form,” noting that “it can amaze and delight guests after a heavy dinner.”

Meanwhile, the late fine-wine authority Michael Broadbent, MW, was famously a devotee of Moscato’s refreshment abilities and dessert properties—as was obvious to any who had been reading his wonderful monthly Decanter magazine columns between 1977 and 2012 (he wrote 433 consecutive monthly columns before he retired!).

Indeed, in his classic Michael Broadbent’s Vintage Wine: Fifty Years of Tasting Three Centuries of Wine, the late Mr. Broadbent made a point of noting that Moscato d’Asti was “a style of wine I love, perfect for puddings” (pudding being the British word for dessert). Or see, for example, this clip of his son, US wine importer Bartholomew Broadbent, discussing his father’s affinity for Moscato d’Asti while reviewing an example from his father’s favorite artisanal producer.]

Moscato is, by design, a simple, a relatively uncomplicated, short-lived sort of wine, but one that is easy to drink, low-alcohol, highly pleasurable, and generally inexpensive. Think of it, perhaps, as a gorgeous wine alternative to soda. The Italians of Asti used to drink it whenever the mood hit—with breakfast, as part of their midday snack, before a meal, or with the dessert course, or after a meal, to quench thirst, or simply to chill of an evening. Adding fresh fruit or fruit juices makes for a briefly diverting and often delicious twist too. It can likewise work a treat added to fruit soups, or fruit salad.

Here are four reasons every well-provisioned wine drinker and host ought to consider reaching for Moscato at some point or other:

#1) Moscato tastes good.

Sure, Moscato d’Asti is a sweet wine, but when its balanced it is not too sweet. Its mild effervescence is generally soft and gentle on the palate, and its delicate flavors and musky perfume tend to entertain at least mildly, if not actively delight, the senses—even if only for a brief, momentary swallow. It is refreshing and, to a degree, palate stimulating.

#2) Moscato is versatile.

Dessert is the part of a meal where Moscato tends to do it best with food, to be sure, but when balanced it works a treat as an aperitif and is gently fizzy and low-alcohol enough to agreeably wash down any number of different courses. It works well with many types of charcuteries, even simple salamis, and tackles spicier foods better than one might think—like arrabbiata sauced pasta, and a variety of spicy Asian and Indian dishes.

#3) Moscato is not very boozy.

Whether enjoyed before, during, or after a meal, or even just sipped poolside, Moscato d'Asti can generally be consumed in greater quantities than most wines without too much ill effect due to its low alcoholic content.

#4) Moscato is inexpensive, and generally offers good value.

Most bottles of Moscato d’Asti are priced more like gourmet coffee at a hipster coffee house than like, say, Coca-Cola, but they are typically closer to Cola in price than other wines of similar quality. Prices vary greatly around the country, but most kosher Moscato can be had for $15 or less for a 750ml bottle. Bartenrua Moscato d’Asti can usually be found for between $15 or less, and the Sara Bee Moscato (though from Puglia, in southern Italy, rather than from the Asti region), is only about $6.

Wine writer and industry consultant Adam Montefiore put it well a couple of years ago in The Jerusalem Post,

Moscato may be drunk literally anywhere, any time. It may be enjoyed at breakfast, brunch, or as an aperitif. It is perfect with spicy Asian food, as a dessert wine to accompany light fruit-based desserts or with cheese. It is probably at its best as an informal party wine. It should be served ice cold, even put it in the freezer for a short time – but don’t forget it there. You can serve it either in a flute or tulip glass, or in a regular white wine glass.

This is a wine that reminds me that wine is meant to be fun, informal and tasty. Just because the wine intelligentsia frown on it, does not mean that real people, who actually drink wine rather than talk about it, are forbidden to enjoy it.

Two Moscato recommendations

As should be expected with vintaged-dated wines, the Bartenura Blue Bottle has endured mild fluctuations in quality and character across vintages, and the period of its production in Pavia also saw some minor but noticeable shifts. In general, however, Bartenura has maintained a remarkable baseline of consistency and good quality. The current vintage available near me is 2020.

Bartenura Moscato d’Asti DOCG, Italy (I picked it up for $11.99; mevushal; 5% abv): This is light, very gently fizzy, delicately sweet, floral, and fruity, offering the usual array of Moscato notes, though perhaps a bit more subtle and a bit lighter than the previous vintage, it nonetheless delivers tasty refreshment. The finish is a little clipped, but still satisfying.

Next up is the Sara Bee Moscato. It is not a Moscato from Asti, but rather a Moscato from Puglia, and only an IGT (Indicazione Geografica Tipica or “indication of geographical typicality”; the third tier of the Italian wine quality pyramid), so really the grapes could be sourced from almost anywhere in the country.

The Sara Bee kosher wine is an exclusive brand to the Trader Joe’s chain of grocery stores. Where we live in the US—in Montgomery County, Maryland—alcohol sales are restricted to County licensed stores, so the local Trader Joe’s does not sell wine; where we live in the UK—in Hendon, in North-West London—Trader Joe’s does not exist. So, I had not tasted Sara Bee in a good long while, and was very pleased to, as it were, rediscover it on my CA trip

Trader Joe’s refuses to divulge any information about the wine. As Nakia Rohde, Public Relations Manager at Trader Joe’s informed me the other day,

Unfortunately, we don’t grant any interviews or comment on products (outside of what you see on our website, Instagram, podcast, etc.) I can share, however, that the Sara Bee Moscato is currently available in many of our stores nationwide.

This is consistent with what I was told back in 2008 or 2009 when I first learned of the wine and reached out to them for details.

That said, the wine is almost certainly made and bottled at the Santero winery, a large industrial-capacity (18+ million bottle per annum) winery in Santo Stefano Belbo in Cuneo, a southwest province in Piedmont, Italy.

The actual wine producer is the Israeli family run company Welner Wines, founded by Shimshon Welner. (My friend Gamliel Kronemer wrote a nice piece on Welner back in 2013.) In keeping with their exclusive arrangement with Trader Joe’s, however, Welner Wines wouldn’t divulge any information about the wine either. They didn’t really even want to be mentioned in connection with the wine, citing Trader Joe’s policy. All a bit silly from a consumer perspective. Especially since Welner Wines list the Sara Bee as one of their products on their own publicly accessible website.

Puglia, where Sara Bee is produced, is a region of Southern Italy bordering the Adriatic Sea in the east, the Ionian Sea to the southeast, and the Strait of Otranto and Gulf of Taranto in the south. Its southernmost portion, known as the Salento peninsula, forms a high heel on the "boot" of Italy.

With no additional details available about the provenance of the wine, all that’s left is to drink it.

Sara Bee, Moscato IGT, Sweet White Wine, Italy ($5.99; mevushal; 5.5% abv): A bit heavier and a bit sweeter than a typical Moscato d’Asti, this is made very much in the same style—fizzy, aromatic, fresh, clean, and very tasty. The signature muskiness, peach, orange blossom and honeysuckle notes play especially well with the bubbly sweetness here, with just enough balancing acidity to keep it fresh and refreshing, while upping the vivaciousness on the palate. For the price, this may be one of the best bargains in kosher wine.

The Sara Bee is a somewhat louder and slightly more lively guest than the comparatively reserved Bartenura in this outing, but either are most welcome at my table, and work a treat while I’m tending the grill on a sunny CA day.

L’Chaim!

About me:

By way of background, I have been drinking, writing, consulting, and speaking professionally about kosher wines and spirits for more than 20 years. For over a dozen years I wrote a weekly column on kosher wines and spirits that appeared in several Jewish publications, and my writing generally has appeared in a wide variety of both Jewish and non-Jewish print and online media. A frequent public speaker, I regularly lead tutored tastings and conduct wine and spirits education and appreciation programs. Those interested in contacting me for articles or events can do so at jlondon75@gmail.com.

In what seems like a lifetime ago, I also wrote an entirely unrelated slice of American history: Victory in Tripoli: How America’s War with the Barbary Pirates Established the U.S. Navy and Shaped a Nation (John Wiley & Sons, 2005).

These days I divide my time between London (UK), and Washington, DC.

Just a couple of things. You mentioned my Black Muscat, and you mentioned Muscat Hamburg. Not everyone would know that Black Muscat is synonymous with Muscat Hamburg in the labeling legalities of the USA, and I specifically used Black Muscat because of the possible negative associations with Germany. Also, Rashi was a competing brand from Yossie Zucker, a previous alumnus of Royal, and possibly the originator of decent quality kosher wine coming out of Italy (the Bartenura Soave and Valpolicella were very marginal). And by the way, also the person who came out with Su Vino Joven, which became Joyvin when Royal took over the brand. Now relegated to also-ran status, Rashi was at one time the good stuff. A tidbit, is that well before Zucker's Rashi, we almost named GAN EDEN the brand name Rashi instead. We were looking for a name which would be compatible with the nonJewish drinker, while still denoting a familiar concept in the Jewish market. Rashi made a significant number of people uncomfortable, sounding a bit like an Indian cult figure (Although I never heard of any cult figures named Maharashi, but that came up enough so we nixed it).

Printing this out for reading on Shabbat. Thanks for the education!!