Red or White Wine for Kiddush and the Passover Seder?

A look at traditional Jewish wine color preferences, followed by a reprise on Beaujolais.

In my previous article on wine for Passover, I opted not to linger on the issue of wine color because the post was long-enough already. Odd as it might seem, however, there is a distinct preference in the Jewish tradition, codified in various scholarly tomes on Jewish law, for red wine over white.

For example, this is how Rabbi Yosef Karo (1488-1575), the author of the authoritative Shulchan Aruch, codifies the preference in Chapter 172 (“The Wines Over Which Kiddush May Be Recited”), section 4:

Kiddush (קידוש; sanctification) may be made over white wine. The Ramban disqualifies white wine for Kiddush, even after the fact, but holds that havdalah (הבדלה; separation) may be made over it. The universal custom follows the first opinion [that white wine is acceptable].

NOTE:

The havdala prayer is recited over a cup of wine to demarcate the end of each Shabbat and the Biblically mandated festivals; separating the holy period just ended from the mundane time just beginning.

Rabbi Moshe ben Nachman (1194–1270) was a medieval Catalonian Jewish scholar, often referred to by Jewish historians as Nachmanides, but more widely known to religious Jews by the Hebrew acronym of his name, Ramban (רמב״ן).

On the one hand, Rabbi Karo’s legal ruling is clear that white wine is perfectly acceptable for kiddush. On the other hand, he also makes a point of highlighting the opinion of the Ramban even though he does not codify it as the law. The clear implication being that the Ramban’s view represents a more stringent or higher standard. The comment about white wine being disqualified “even after the fact” is an artifact from the language used in the source material. The Ramban was commenting on a Talmudic discussion (Bava Batra 97b) about wines that were deemed less than ideal for use in religious service, but which were deemed acceptable “after the fact” if used in error or in exigent circumstances. His more stringent view singled out white wine.

Upon this ruling Rabbi Yisrael Meir ha-Kohen Kagan (1838 – 1933), more widely known as the Chofetz Chaim (after one of his more popular books), comments in his work, the Mishnah Berurah:

According to all opinions, it is a mitzvah, initially, to seek after and to use red wine. But this opinion holds that if one has no red wine or if it is not of a good quality, it is permitted, even as a matter of initial preference, to make Kiddush over white wine.

So, while strictly speaking one is not absolutely obligated to use red wine, it is clearly preferable to those traditionally inclined. It is likely for this reason, at least in part, that kosher consumers seem to toe the line.

For example, according to Dovid Riven, president of KosherWine.com, the leading internet retailer of kosher wine, overall sales are roughly three bottles of red wine for every one bottle of white. Similarly, Gabriel Geller, Director of Public Relations and Advertising and Manager of Wine Education with the Herzog family’s Royal Wine Corp., the largest producer, importer, and exporter of kosher wine in the United States and Europe, indicates that sales of red wine amongst their Jewish clientele—attempting here to factor out the massive sales of Bartenura Moscato to the non-Jewish market—was also about 70-75% overall.

What is The Difference Between Red Wine and White?

This will likely seem overly basic to most, but just in case…

Wine is an alcoholic beverage made with the fermented juice of fruit, principally grapes. The fruit is crushed to release its juice which naturally contains sugar and so is more susceptible to yeast, ambient or cultured, which will attempt to consume the sugars, resulting in the production of alcohol and carbon dioxide. One of the basic tasks of a winemaker at this stage is to promote this process as hygienically, as effectively, and as efficiently as possible.

When producing white wine, the juice will generally be separated from the crushed grapes. In the production of red wine, however, the grapes are fermented together with the crushed grape skins and related solid matter. The color of red wine is the result of contact with the red/blue anthocyanin pigments found in the skins of darker-skinned grapes.

While the juice of the grape is initially clear, it begins extracting color from the grape skins almost immediately. Perhaps the most important factor influencing color is the strength of the natural acidity of the grape juice.

As my California winemaker friend Craig Winchell, formerly of the Agua Dulce Winery and before that of the now legendary Gan Eden Winery, explains it, “the hue is largely dependent on the acidity of the wine, which in reds tends to be between 3.45 (redder) and 4.1 (bluish)” as measured by pH.

pH, or "potential of hydrogen,” is a logarithmic scale of measurement of the concentration of free hydrogen ions (protons) in a solution. The relationship between hydrogen ions and pH is inverse—a high concentration of hydrogen ions result in a low pH, and low levels of hydrogen ions yield a high pH. This provides a useful measurement since acidity releases hydrogen ions in solution. Meaning that the stronger the acidity in the solution, the greater the concentration of hydrogen ions. So pH essentially provides a measure of the strength of the total acidity in solution, such as grape juice or wine.

As Winchell put it,

Higher pH goes to a bluish end of the scale, eventually at very high pH it would turn green, though at far higher pH than would be found in wine. The point being only that anthocyanins go from bright red to colorless depending on pH.

In other words, generally speaking, the more acid in the grape juice (of ripe grapes), the brighter red the color of the wine will be.

Winemakers will generally choose specific varieties of darker-skinned wine grapes (Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, Syrah, etc.) to produce red wines, and specific varieties of lighter-skinned wine grapes (Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, Pinot Grigio, etc.) to produce white wine. White wine grape skins are not actually white; they tend to run along a range from pale green to straw, to a pale copper, to a deep gold, to something more like amber.

Although called “red” such wines may vary significantly in color from almost black to a dark pink (though in the eyes of Jewish law, according to most authorities, even very lightly pinkish wines, such as rosé, or even a mix of mostly white wine with a little red wine for color, also count as “red”). The various hues of red are determined by such elements as the variety of grape selected, the quality of the grapes obtained, and the methods of production chosen by the winemaker.

As an interesting aside, the Oxford Companion to Wine notes that,

It has been only since the development of bottles suitable for ageing wine that red wines have been seen in any sense superior to white.

Roughly speaking, sustainable widespread commercial production of bottles suitable for ageing can be dated to around the end of the 17th century.

Red Wine in the Bible

This general preference for red is, perhaps, not too surprising, when one considers that red wine is favorably mentioned in the Bible. While most of the hundreds of Biblical references to wine say nothing at all about its color, the few that do mention color, explicitly refer to the color red.

Consider, for example, Jacob the Patriarch’s blessing to his son Judah (Gen 49:8-12). The first three verses (8-10) speak to the Divine promise of sovereignty over his brothers and the future kingdom, and then the next two verses (11 & 12), which mention red wine, are a blessing for the fecundity of wine production in the Hills of Judea. The imagery is arresting:

11. Binding his foal to the vine, and his ass’s colt to the choice vine; he washes his garments in wine, and his clothes in the blood of grapes;

12. His eyes are red with wine, and his teeth white with milk.

The next notable reference to red wine in the Bible is a bit more of a downer but is nonetheless seized upon to great effect by the Talmud. In Proverbs 23:31 (I’ve also included 23:32 for context) it says,

31. Look not upon the wine when it is red, when it sparkles in the cup, when it goes down smoothly;

32. In the end, it bites like a snake, and stings like a viper.

Verse 32 makes for one hell of a tasting note! At any rate, this section of Proverbs is an admonishment against excessive drink yet is widely interpreted by the Rabbinic Sages as proof that red wine is desirable and, indeed, the most important sort of wine. After all, the verse said red rather than white, and makes clear that the wine is both enticing and potent.

Red Wine in the Talmud

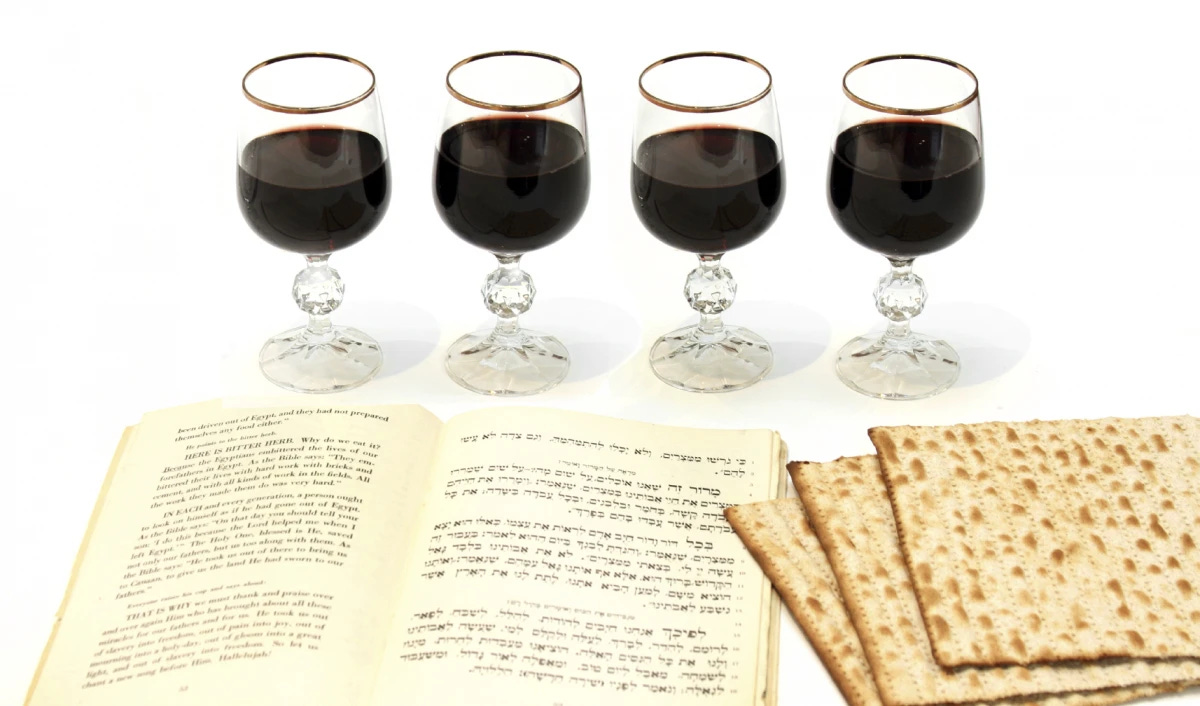

The Talmud Yerushalmi (compiled c. 350–400 CE) records the following discussion (Pesachim 10:1) regarding the laws of the obligatory arba kosot (ארבע כוסות), or four cups of wine, at the Passover seder (the ritual banquet at the start of the holiday):

Rabbi Chiyah stated: [Regarding] the arba [kosot], one may fulfill his obligation either with unmixed or mixed [wine], so long as they have the taste and appearance of wine.

Rabbi Yirmeyah said: The Mitzvah is with red wine. What is the reason? “Look not upon the wine when it is red.”

The Talmud Yerushalmi is not the authoritative final word but serves as an early marker in favor of red over white, and Rabbi Yirmeyah’s pronouncement is taken as an elucidation of Rabbi Chiyah’s comment about the “appearance” of wine. That is, so long as the wine recognizably tastes of wine (which is thought to mean that it has noticeable alcohol) and is red, one may thereby fulfill their arba kosot obligation with it.

This same verse from the book of Proverbs is also used again as a related prooftext in the Talmud Bavli (the compilation of which was finalized c. 500 CE), more commonly referred to as simply the Talmud—the primary and essential text and source of all Jewish law, religious thought, and rabbinic intellectual endeavor. As the Talmud (Pesachim 108b) relates:

Rabbi Yehuda says: [wine used for the arba kosot] must have [the] taste and appearance [of wine]. Rava said: What is the reason [behind the opinion of] Rabbi Yehuda? As it is written: “Look not upon the wine when it is red.”

The discussion there does not emphasize the color, but the same verse is used to explain Rabbi Yehuda’s premise that the wine must have the taste and appearance of wine to fulfill the arba kosot.

The pattern is unmistakable. And so, this same verse re-appears once again in a later Talmudic discussion (Bava Batra 97b; referenced above in connection to the commentary of the Ramban) regarding which wines are deemed acceptable for use in reciting the kiddush.

Wines Fit for the Altar

This Talmudic sugyah (סוגיא; passage from the Talmud)—generally understood more expansively as ‘a distinct matter for consideration in discussion, thought, or study’—is a bit involved, but for this discussion it is worth at least briefly examining.

The underlying basis for this sugyah (on Bava Batra 97b) is the following opinion:

Rabbi Zutra bar Toviyya said in the name of Rav: One may not recite the kiddush of the day except over wine that is fit to be poured upon the altar.

The “altar” reference is to the wines that were poured daily as a libation sacrifice that accompanied most of the animal sacrifices (see also Bamidbar 15:1-16; 28:7-31) back in the days of the Beit HaMikdash (בית המקדש), Holy Temple in ancient Jerusalem.

The Temple service was the primary form of Jewish worship in Temple times. Indeed, the Temple was both the bedrock and backbone of all Jewish religious life—right up until the Roman conquest and destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE. Despite its disappearance two thousand years ago, the Holy Temple—and the messianic promise of redemption, return, the rebuilding of the Holy Temple, and the return of the Temple service—remains a constant and ever-present trope in daily Jewish prayer. The formal incorporation of wine into Jewish life was primarily derived from these daily wine libations, so using that context as the source for the requirement of kiddush makes sense.

Thus the 12th-Century sage Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon (aka Maimonides) codifies that

Kiddush may be recited only on wine that is fit to be offered as a libation on the altar.

So, the Talmud considers various possibilities as to which wines might be excluded by this principle, and thereby establishes (on Bava Batra 97b) the related principle that

if one brought [a less ideal wine as a libation and yet] it is [deemed] valid [after the fact], [then] we [should certainly] also [be able to use it for kiddush], even preferentially.

The notion being that anything that was ultimately good-enough for the altar in the Holy Temple, the holiest location in Jewish life, then it is certainly fully acceptable for the kiddush recited in our homes, the holiest place in the life of every Jewish family. At the end of the sugyah, the Talmud relates (Bava Batra 97b) the following exchange:

Rav Kahana, father-in-law of Rav Mesharshiyya, asked Rava: [regarding] white wine, what is [the ruling]? He said to him “Look not upon the wine when it is red.”

Owing to the slight ambiguity of the context, and the typically cryptic nature of the exchange as memorialized by the Talmud, there is a dispute as to whether Rava’s apparent dismissal of white wine is meant to exclude it from use on the altar or also from its use in the kiddush. As is so often the case, the commentators understanding of the context and applicability of this passage of the Talmud plays out in their halachic decision.

For example, Rabbi Shmuel Ben Meir, the grandson of Rashi—better known by the acronym of his Hebrew name as the Rashbam [רשב"ם]—comments here that Rava is only talking about libations upon the altar, not kiddush. So, white wine is therefore acceptable for kiddush. He notes, though, that red is generally considered preferable to white as the verse makes plain that red wine is superior owing to its more intoxicating nature.

Meanwhile, as noted above by Rabbi Yosef Karo, the Ramban disagrees. He argues instead that Rava means to exclude white wine for both the libation sacrifice and also for the kiddush, and accordingly rules against the use of white wine for either, even after the fact.

The Ramban’s view is evidently a minority opinion. Most authorities embrace Rabbi Karo’s ruling that white wine is perfectly acceptable. Yet they all make clear, in deference to the stringent view, that red is preferable all things being equal.

What About the Wine for Passover?

When it comes to the themes of Pesach, there are those who find additional symbolism in using red wine especially for the arba kosot (ארבע כוסות). These are the four cups of wine consumed at the seder (סדר), the ritual banquet, on the first night—first two nights outside of Israel—of Pesach (פסח; Passover).

For example, Rabbi Isaac ben Moses of Vienna (c. 1200-c. 1270), more popularly known by the name of his work on Jewish law, Or Zarua (אור זרוע; “Light is Sown” a quote from Psalm 97:11), writes:

Red wine as a remembrance for Pharaoh who slaughtered the babies (and bathed in their blood) when he was suffering with leprosy. And furthermore, it is a remembrance for the blood of the Korban Pesach [the Paschal Lamb] and the blood of milah [circumcision].

Similar sentiments are found in the rulings of many later authorities, including the Pri Megadim (by Rabbi Joseph ben Meir Teomim; 1727–1792), the Kitzur Shulchan Aruch (Rabbi Shlomo Ganzfired, 1884-1886), and the Mishnah Berurah.

Interestingly, the Rabbi David Ha-Levi Segal (1586–1667), better known as the Taz (ט"ז, the Hebrew acronym for his work on Jewish law, Turei Zahav or “Rows of Gold”), made an exceptional ruling in light of the persistent persecution of Jews of his time in 17th Century Poland. On this (above) ruling of Rabbi Karo, Rabbi Segal adds:

We now refrain from using red wine because of the false blood libel.

Similarly, the Kitzer Shulchan Aruch (in the same section referenced above), writes:

In backward and ignorant countries, where people make slanderous accusations, Jews refrain from using red wine on Pesach.

The same sentiment is repeated by Rabbi Kagen in his Mishnah Berurah (also in the same section referenced above) comments:

In localities where it is common for the gentiles to fabricate libelous lies, one should refrain from taking red wine for these cups.

NOTE:

The blood libel accusation has plagued Jewish life in the Diaspora for centuries. This is the lie that Jews murder Christian children to use their blood for religious ritual purposes. The false allegations have often been an excuse for pogroms and mob violence against Jews and Jewish communities. Indeed, two sons of Rabbi Segal, named Mordechai and Shlomo, were martyred in the devastating pogroms in Lemberg in the spring of 1664; all part of the evil persecutions instigated by Bohdan Khmel’nyts’kyi.

Anecdotally, I know folks both in Israel and the United States of America who, motivated by the blood libel concerns of their forebears, prefer red wine for the arba kosot in order to proclaim at their seder that they do not fear the anti-Semites of old, and that the contemporary power relationship they enjoy means they never again have to curtail their religious expression.

So, How Best to Proceed?

In practical terms, while there are some who have the custom to eschew red wine for the arba kosot owing to the history of persecution in the areas from which their family customs evolved, Rabbi Karo’s earlier published codification remains the primary guidance. In chapter 472 (“The Laws Concerning Reclining and The Drinking of the Four Cups of Wine”), section 11, he writes:

It is a mitzvah to obtain red wine

To which Rabbi Moshe Isserless (1530-1572), in his gloss on the Shulchan Aruch (included in every published edition of the Shulchan Aruch since 1578), adds:

(unless the white wine is superior to it).

So, as with wine for the regular kiddush, Jewish law explicitly allows the use of white wine for the arba kosot, though red is preferred. As in so many other regards, Sephardim tend to follow the directives of Rabbi Karo, and will use red even when superior white wines are available, and Ashkenazim tend to follow the guidance of Rabbi Isserless, selecting whichever wine is thought superior. In the modern context in which world-class kosher wines are readily available in either red or white, one need not compromise on objective qualitative terms, and can factor in style and personal preferences if so inclined.

It is interesting to note, however, that the issue of quality was deemed significant enough to Rabbi Isserless for him to emphasize it in his gloss. This concern over quality, it seems to me, may be combined with an earlier ruling by Maimonides which I mentioned in my previous article. Maimonides writes:

These four cups [of wine] should be mixed with water so that drinking them will be pleasant, [the proper ratio of which] all depends on the wine and the preference of the person drinking.

Combining these thoughts—that quality trumps traditional color preferences, and that one’s personal taste and the pleasure of the experience matters—leads, arguably, to the proposition that one may fulfill the obligation of the arba kosot over any kosher wine, regardless of color, so long as it is of high quality and pleasing to the one consuming it.

What I’m Drinking Right Now

While scribbling my thoughts down here, I am enjoying a chilled glass of the Abarbanel, Beaujolais Villages, Château de Pougelon, Batch 90, Old Vines, 2018. So, I’m also taking the liberty of updating and re-posting here an older article on this wine first published by the Jewish Week, and in a much shorter version also by the Washington Jewish Week.

I have never been shy about my love affair with the infectiously joyous, essentially flirtatious, wonderfully refreshing wines of Beaujolais, France, and the Abarbanel Beaujolais Villages has invariably been one of the few available kosher options on the American market.

Made from the Gamay grape, formally known as Gamay Noir à Jus Blanc or black Gamay with white flesh, Beaujolais wines have earned a solid reputation for enhancing meals, and for their “delicacy, freshness, smooth succulence and perfumed immediacy” as wine writer Andrew Jefford memorably put it.

While Beaujolais fell out of fashion in the 1990s due to sloppiness and overproduction of Beaujolais Nouveau, the region’s wines have clawed their way back into the good graces of wine geeks and sommeliers by focusing on terroir and the unvarnished virtues of the Gamay grape.

At its best, Beaujolais wines are, to quote Jefford again, “poised, fragrant, refreshing, and drinkable, yet ballasted with a fine mesh of tannic complexity, too.”

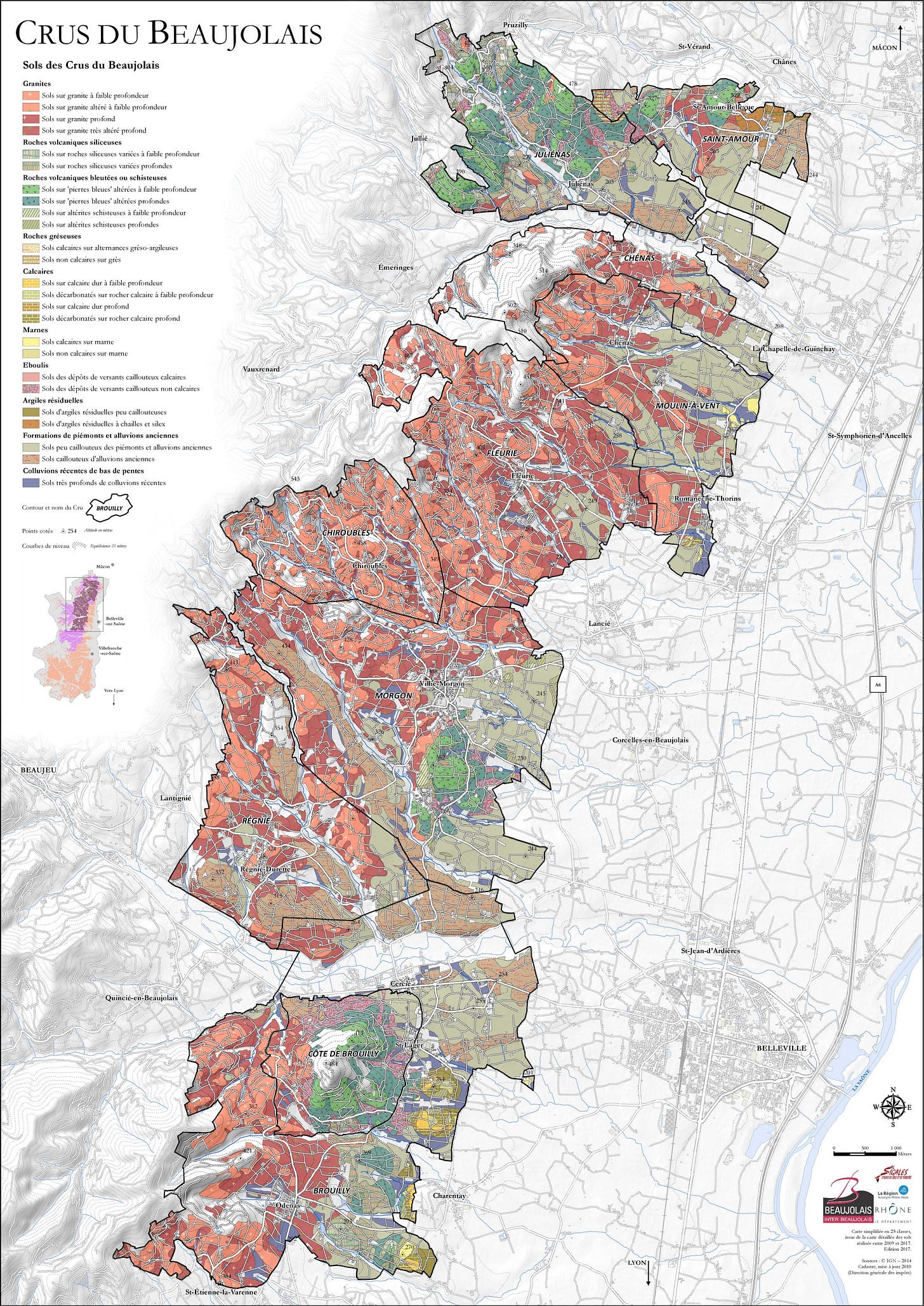

Just 34 miles long and seven to nine miles wide, the Beaujolais region lies in east-central France, just north of Lyon and south of Burgundy. In terms of government administration, the province of Burgundy technically includes part of Beaujolais—and so there are some who naturally consider the Beaujolais wine region as yet another part of greater Burgundy. It is not. Beaujolais has its own history, soil types, topography, climate, grape varieties, winemaking styles and personalities. The difference between the wines sold as Burgundy and those as Beaujolais are as great as chalk and cheese. Further, Beaujolais is mostly in the Rhône département, and so Burgundians consider Beaujolais wines as les vins du Rhône. The general convention, followed here, is to consider Beaujolais as its own thing entirely.

Indeed, whether drinking simple Beaujolais (which can come from any of 72 communes), Beaujolais Villages (which comes from any of 38 villages in the northern Haut Beaujolais), one of the acclaimed Cru Beaujolais (which can only come from one of the ten villages in the foothills of the Beaujolais mountains), or the ubiquitous Beaujolais Nouveau (easily the area’s most famous wine style), the wines of the Beaujolais region are readily identifiable, especially in their youth.

For Beaujolais wines are nearly all representative of a unique style of delicious, fruity, fresh, red wines that have the weight, structure, and balance of a white wine. Beaujolais is best served slightly chilled.

As I’ve noted before, the availability of kosher Beaujolais in the United States is enjoying something of a renaissance these last few years, thanks entirely, now, to the good folks at KosherWine.com. Wine importer Howard Abarbanel, a friend, had initially championed Beaujolais in the American market, and consistently did so until his well-earned retirement earlier this year, after 30 years in the Business; he sold the brand to the JCommerce Group, the parent company of KosherWine.com.

For years, the longest and most consistent source of kosher Beaujolais wines available in the US was from The Abarbanel Brand Wines, produced by Château de la Salle. Alas, the last vintage of theirs to hit the US was the 2012, and then the proprietor retired from the wine business before another suitable vintage was produced. As Howard Abarbanel put it to me at the time,

They ripped-up most of their vineyards and put in a golf course and turned the Château into a hotel, leaving me in the lurch for the past few years without a quality Beaujolais supplier.

Back in late 2016, I had the opportunity to interview Yves Royé, proprietor of Château de la Salle. He said that he first began producing kosher wine in 1979, prompted by “a caterer friend, Daniel Jouve, producing just 4,000 bottles under the supervision of Rabbi Jacques Poultorak of Lyon.” The kosher side-business worked out very well. He first began exporting initially through the Royal Wine Corp., and then switched to Abarbanel. By 1985, according to the LATimes (M. Royé couldn’t recall the exact figure in our conversation), he was on track to sell 50,000 bottles. Depending on the vintage, however, he generally produced on average “15,000 to 20,000 bottles” of his kosher wine. In 2015 he sold his primary business, NPK, and then his wine interests. In retirement, he and his wife turned their Château into a rather fine looking hotel.

NOTE:

A shorter version of this interview with M. Roye appeared in the Washington Jewish Week back when I had my weekly column in their print edition.

My old columns were always posted online as well, but the archive isn’t reliable. For at some point they “upgraded” their website, resulting in a technical glitch whereby my name was dropped from many of my articles, and replaced with the names of random staff writers—some of whom had already left the publication by then. I never fully understood the nature of the technical problem, but I did try to get the attribution/by-line issue resolved. Alas, the issue persists for an uncertain number of my articles.

I’ve no doubt that Mr. Justin Katz is a gifted journalist, but he did not write this installment of my column that now bears his name—or, for that matter, any of the others in the L’Chaim column/series. Whatever…

Victor Kosher Wines eventually filled the gap with a lovely Louis Blanc selection Cru Beaujolais from Côte de Brouilly (produced by Domaine La Ferrage). The category got its biggest US push in decades when Dovid Riven, the then savvy wine manager of the Washington-based JCommerce Group—the parent company of the online kosher wine retail websites JWines.com and KosherWine.com—began bringing in a Beaujolais Nouveau. [Riven is now the Executive vice President and Wine Buyer for JCommerce, and the President of KosherWine.com.]

Under Riven, the JCommerce Group next took over the import of the Louis Blanc Côte de Brouilly, and then also brought in two additional Louis Blanc Cru Beaujolais wines, the Juliénas and the Moulin-à-Vent. (They have since added a Morgon, and, alas, for now the Moulin-à-Vent is gone.) All lovely wines that I very highly recommend! Indeed, every well-provisioned wine lover and host should incorporate Beaujolais into their routine.

Abarbanel later brought the Beaujolais Villages category back to the US kosher wine catalog with a real beauty of wine, produced by the well-regarded Château de Pougelon, situated in Saint Etienne des Oullières, in the heart of Beaujolais.

“I found them,” noted Abarbanel at the time, “it was a year-long effort to convince them to allow a rabbinic invasion!” It wasn’t an easy search either. “I wasn’t going to bring this wine back,” remarked Abarbanel, “unless the quality was equal or better to what we were doing for the last 20 years prior.”

Fortunately, Château de Pougelon is “easily on a par with de la Salle,” and “they’re big and well-regarded producers of non-kosher Beaujolais Villages and Cru Beaujolais.”

Originally founded in 1662, the contemporary winery is part of the fifth generation family-owned Vins Descombe group, producing wines from 29.65 acres of the Château de Pougelon’s own vineyards in the Beaujolais Villages and Brouilly appellations. Their Beaujolais Villages vines are “old vines,” from between 40 to 98 years old, resulting in distinctive, quality wines.

Vins Descombe is “owned by a family of entrepreneurs,” Bernard Bouteillon, the then export manager for Vins Descombe told me, “and we are always looking at new opportunities, new markets, new ideas.” When Abarbanel approached them, it piqued their curiosity.

“Producing a Beaujolais-Villages kosher was a challenge,” noted Bouteillon, “and we love that this challenge complimented our larger challenge, embraced three years ago, of selling to the US market. So, we went into it. Fully.”

It “took many contacts to understand the principles of kosher wines,” explained Bouteillon, “and through it [we] learnt a lot about the Jewish culture and the related needs of something we have in common: the wine culture.”

Further, he said

the process needed adaptation from our company and own process, but under the guidance of the Beth Din of Lyon we could understand it and implement what was needed. Overall, there is nothing complicated. It is only a different way of doing it. And we will be happy to do it again and develop our kosher production in the future.

At the time, their oenologists compared their regular and kosher Beaujolais Villages, and “are very pleased with the kosher wine!”

“Indeed,” explained Bouteillon,

the kosher wine is made under a 100% traditional winemaking process, while the conventional Beaujolais Villages is a blend of tanks, some of them having been made under a thermos process. It appears that the 100% traditional winemaking allows [for] a better expression of the exceptional 2018 vintage, bringing the fruit to the front. The natural structure given by the characteristics of the 2018 vintage, wet in spring and very hot and dry throughout summer and early fall, comes on top to make a bodied yet expressive, long, and velvety wine. Back to the roots of the Gamay grape!

Adding, “we really hope consumers and wine lovers will take as much pleasure drinking it as we had in doing it!” Indeed, I certainly did!

My tasting note:

Though four years past vintage, this remains playfully vibrant and clean. Bright crimson with lustrous deep purple highlights, this delightful wine offers appealing outdoorsy aromas of flowers and red and black summer fruits, leading to yummy flavors of raspberries, blackcurrants, blackberries, cherries, subtle blanched almonds, a little violet, and all with a light strawberry overlay. Well-balanced with nice acidity and mild tannins.

Though now showing a little bit of age, this can play down as a simple but oh-so-pleasurable quaffer to accompany light meals, picnics, or a pre-dinner cocktail hour, but can just as easily play up to hearty meat meals with just enough felicitous complexity to hold the attention. This is a lovely Beaujolais Villages!"

L’Chaim!

About me:

By way of background, I have been drinking, writing, consulting, and speaking professionally about kosher wines and spirits for more than 20 years. For over a dozen years I wrote a weekly column on kosher wines and spirits that appeared in several Jewish publications, and my writing generally has appeared in a wide variety of both Jewish and non-Jewish print and online media. A frequent public speaker, I regularly lead tutored tastings and conduct wine and spirits education and appreciation programs. Those interested in contacting me for articles or events can do so at jlondon75@gmail.com.

In what seems like a lifetime ago, I also wrote an entirely unrelated slice of American history: Victory in Tripoli: How America’s War with the Barbary Pirates Established the U.S. Navy and Shaped a Nation (John Wiley & Sons, 2005).

These days I divide my time between London (UK), and Washington, DC.