NOTE: This was originally an old article of mine published in the February 16, 2017 // 20 Shevat 5777 issue of a now long defunct Washington, DC area Jewish newspaper called, Kol HaBirah—see here for a flipbook copy of the original article as printed. It seems still relevant, so I thought I’d repost it, with substantive tweaks and additions to freshen it up.

Have you ever wondered why a bottle of wine costs what it does? One of the perennial complaints amongst kosher wine consumers is the general rise of kosher wine prices.

There is, of course, a school of thought that maintains that most complainers engage in complaining because, well, the “complaint” is simply their preferred mode of expression.

Like the old joke about the elderly Jewish man who kvetches loudly “Oy, am I thoisty!” until a bystander who can no longer stand the complaining fetches him water to quench his thirst, to which the old man after gulping down the water responds just as loudly, “Oy, was I thoisty!”

Whether those who query rising prices are merely kvetching, or genuinely want to understand why, isn’t so essential. The question remains a good one: why does a bottle of wine in America cost what it does?

Jeff Morgan, the vintner and co-owner of the kosher Covenant Winery, in Berkeley, California, once usefully addressed this question in a blog-journal post on the Covenant Winery website, in a short essay: “Truth in Wine: what is a bottle of wine worth?” [Alas, no longer available online best I can tell.]

Morgan began by offering the safest and surest advice on wine buying—his secret to success as a wine consumer is first, “not to buy wines I can’t afford” and second, “not to drink wines I don’t like.”

Exactly so.

I’ve advocated the same for as long as I’ve been scribbling about booze. At any rate, Morgan tackles the “truth” about wine prices by clearly explaining some of the factors involved, the central feature of which is the three-tier system.

Alcohol Regulation in the United States

The United States market for alcoholic beverages is structured around what is called the three-tier system of distribution to the consumer—the great importer Joe Dressner (1951-2011) used to call this the “three-tier schnook system” (his April 13, 2001 explanatory blog post on this is awesome!).

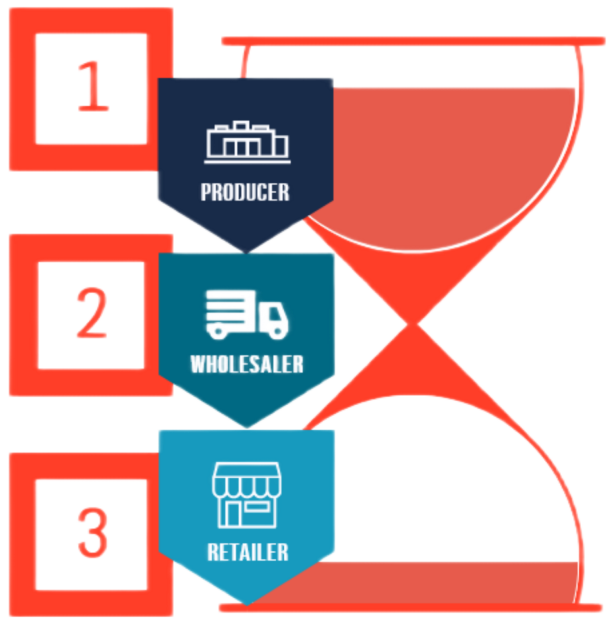

The three tiers are:

Importers or producers

Distributors

Retailers.

NOTE: If American history and the American regulation of booze are of no interest, readers can safely jump to the next section to pick-up the primary thread of wine pricing.

According to the National Alcohol Beverage Control Association (NABCA)—the national association that represents the various Control State Systems that directly control the distribution and sale of beverage alcohol within their borders:

“The three-tier system is the bedrock to the U.S. alcohol regulatory structure. The traditional three-tier system is an hourglass-like structure with producers at the top, funneling down to the wholesalers in the middle where tracking of tainted alcohol products and excise alcohol tax collection occurs, and then fanning back out to retailers who get the product to the consumer.

“The three-tier system operates in the background ensuring product safety, tax collection and preventing market domination by restricting any one tier from having financial interest in another, a common practice in the pre-Prohibition era that led to aggressive sales tactics and heavy consumption.”

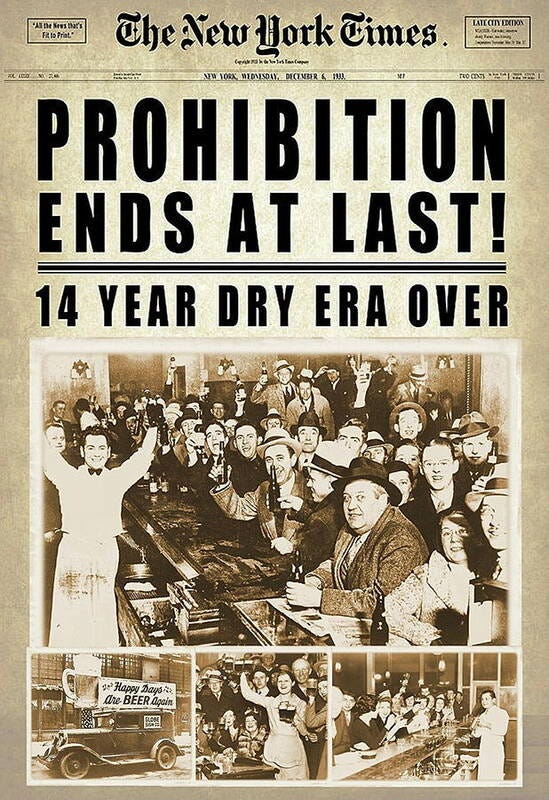

This clunky regulatory structure emerged following the end of Prohibition, that period (Jan 17, 1920 – Dec 5, 1933) during which the United States Federal Government prohibited the general production, importation, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages. The 21st Amendment of the US Constitution —the sole function of which was to “repeal” the 18th Amendment which made Prohibition the law of the land—was finally ratified by the requisite number of states on December 5th,1933, thereby de-criminalizing alcohol again.

After Repeal, the alcohol beverage industry was subject to Federal regulation under the 1933 National Industrial Recovery Act’s codes of fair competition. To sort out the immediate mess, President Roosevelt created the Federal Alcohol Control Administration to administer the codes of fair competition, but legal challenges weren’t far behind.

In May 1935, the Supreme Court struck down the provisions of the National Industrial Recovery Act as unconstitutional. So in August 1935, Congress enacted the Federal Alcohol Administration Act to regulate the alcohol industry. It is upon this statutory authority that the U.S. Treasury Department’s Alcohol Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) operates today.

The TTB, created in 2003 by the Homeland Security Act of 2002, is the Federal agency that enforces regulations and collects taxes on alcohol, tobacco, firearms, and ammunition. Ask any American booze industry insider about the TTB, and you’ll get an earful—good, bad, and ugly—about the variously frustrating, confusing, burdensome, and, at times, even maddening rules and regulations.

Warning: Nerdy booze-history follows

As infuriating as the TTB’s rules and regs may seem to some today, the legal edifice it represents and enforces is still better than things were under Prohibition. As the Baltimore Sun’s H.L. Mencken wrote at the time the 21st Amendment was ratified:

“Prohibition went into effect on January 16, 1920, and blew up at last on December 5, 1933—an elapsed time of twelve years, ten months and nineteen days. It seemed almost a geologic epoch while it was going on, and the human suffering that it entailed must have been a fair match for that of the Black Death or the Thirty Years’ War.”

Interestingly, however, the decision to repeal Prohibition was not unanimous. Congress proposed the 21st Amendment to the U.S. Constitution on February 20, 1933. Michigan became the first state to ratify it on April 10, 1933. The amendment was fully ratified only on December 5, 1933, when Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Utah—then the 34th, 35th, and 36th states to do so—voted in favor. At the time, the U.S. had 48 states.

Maine voted for repeal the next day, on December 6. Montana eventually followed on August 6, 1934, likely feeling obligated to complete the process due to the expense and effort of organizing the ratifying convention, even though the issue was already decided nationally, rendering the outcome of their convention of no consequence.

But what about the other 10 states?

Well, on November 7th, 1933 the voters of North Carolina rejected the idea of even convening a convention to consider the amendment, and the voters of South Carolina voted on December 4th against the amendment to repeal Prohibition! Even more bizarrely, the states of Georgia, Kansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Nebraska, North Dakota, Oklahoma, and South Dakota took no action at all to even so much as consider the amendment.

Think of this the next time you struggle to comprehend unwelcome U.S. election processes and results. The United States of America is, indeed, a very diverse nation.

Understanding wine price dynamics

So, how does this three-tier system impact wine pricing?

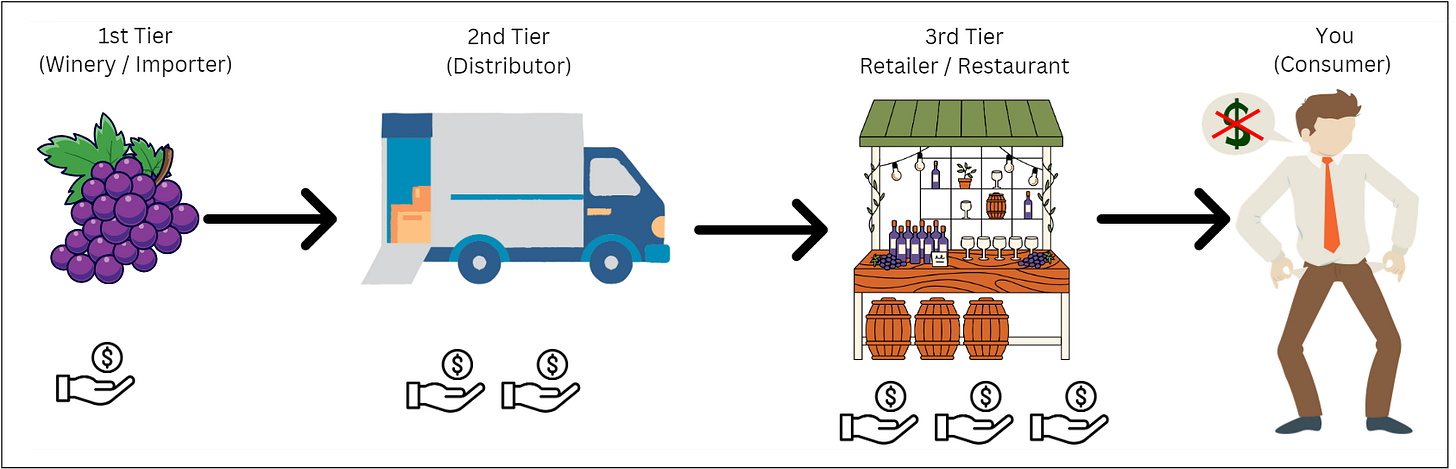

Typically, the wine producer or importer (1st tier) sells to a wholesale distributor (2nd tier), who in turn sells to restaurants and retailers (3rd tier), who then sell to consumers. Each of the three tiers needs to make a profit, ideally from the final price paid by you, the consumer. So, each tier prices the wine based on the cost of the previous tier, with the increments determined by market forces.

As Jeff Morgan explained in his blog essay, wineries typically sell to distributors at half of the final retail price.

This is known as the FOB, or “freight on board”, and represents all the costs associated with the product until it is delivered to its designated destination, which in this case is the distribution or 2nd tier in the three-tier system.

So, the FOB price is all that the winery will get per bottle out of the entire arrangement, and so must encompass all the winery costs—from vineyards to facilities and equipment, labor (from field hand to upper management), any loans, costs of maintenance (to land, equipment, and labor), general administration, and, of course at least some margin of profit. Putting the proper FOB together can be as much art as science, given the many variables of the wine industry. As you might imagine, not all wine producers get this right, especially less seasoned players.

So, for example, if the FOB is $20—that is, the distributor pays the winery about $20—the distributor will then sell to the retailer or restaurant at about a 33% markup, or about $27. The retailer will then add roughly a 50% markup on their cost. So, a $40 bottle of wine at your favorite wine shop represents only around $20 to the winery.

Restaurant markups vary widely as determined by their costs, but are often twice the retail price—so that $40 bottle might be $80 or so in a restaurant. The winery will still only clear $20 for the bottle.

In practice, however, this tends not to be so tidy.

“With all the variables,” Morgan wrote, “it’s impossible to say with any certitude what profit a winery is going to make on this wine. But it’s very possible that the total investment in that bottle—given all the costs of doing business—is perilously close to the price that the winery charges for it.”

This is to say, it’s a tough racket to do well in.

I’ve seen estimates that when demand is very high, and business is booming, a commercially successful winery’s profit margin could be 30-50%, but when business is low and slow, the profit margin could be 0-15%. Even still, the variables can, alas, be high and punishing.

“Suffice it to say,” Morgan noted, “that I’ve been in the wine business for nearly 30 years, but I have yet to make any ‘easy money.’ In fact, for the first 10 years of Covenant, I made no salary. Instead, I made wine for other people and wrote books to make ends meet.”

Even though some wineries get lucky and make good money quickly, “the rest of us,” he says, “are generally happy to stay afloat and make wines we are proud of—at a number of different price points.”

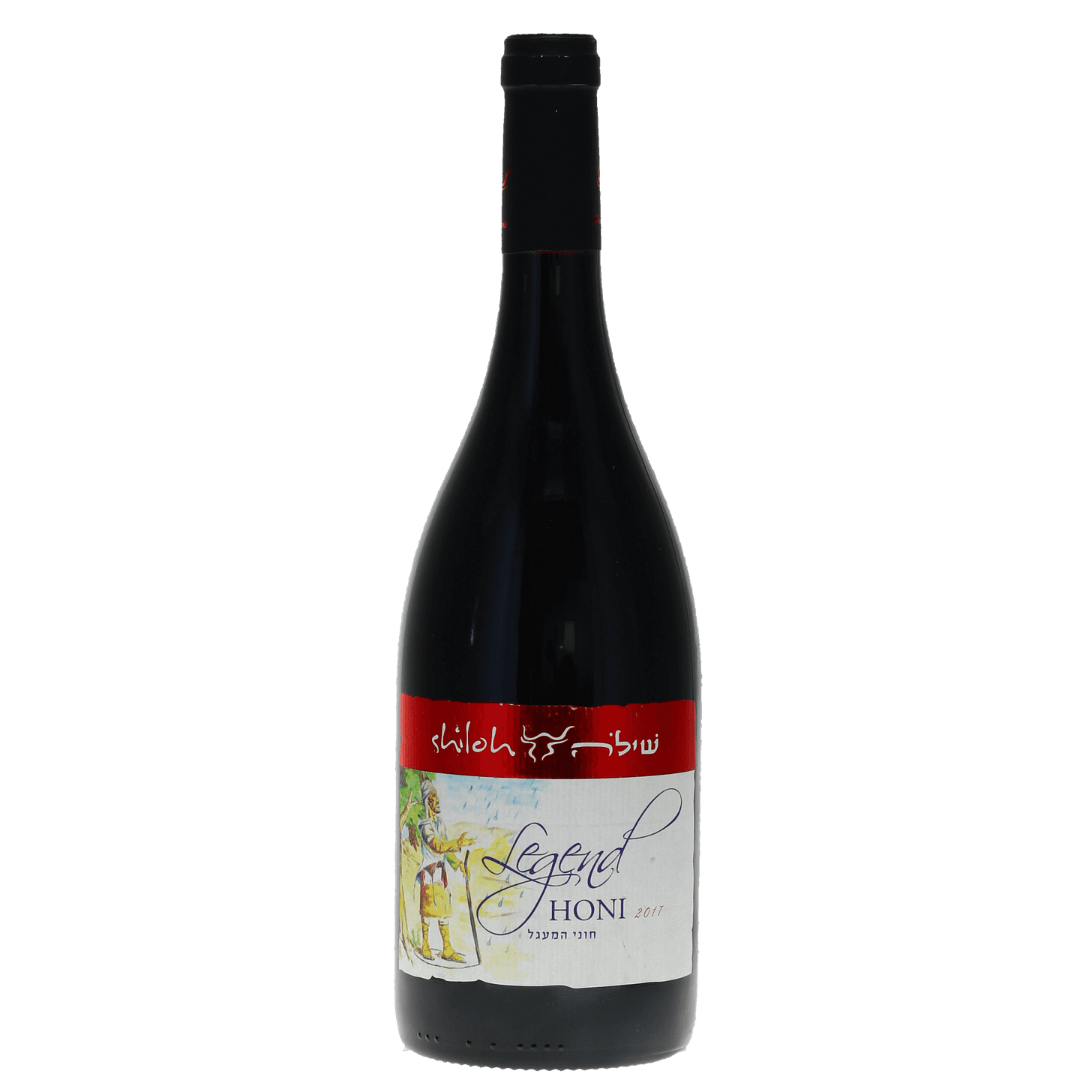

As I updated this article, I drowned my complaints with a glass of the absorbing and rewarding 2021 Legend Honi from the Shiloh Winery.

Part of Shiloh's “Legend” series of blends, the name “Honi” is an homage to the 1st Century BCE sage Choni HaMa’agel [חוני המעגל or Choni the Circle-drawer] whose legend was established for posterity by the Mishna (Ta'anis Chapter 3, paragraph 8) for his successful stand-off with God that yielded desperately needed rain as a respite for the drought-induced parched earth—though Choni has a rich history beyond that story as well.

The ’21 Honi is still young and tannic but is smooth, rich, and complex, with aromas and flavors of black fruits, tobacco, eucalyptus, and some lovely spice notes. This is a seemingly well-balanced blend of 61% Cabernet Sauvignon, 35% Cabernet Franc, and 4% Malbec aged in French oak for 15 months—always Cab based, previous vintages have had very different blends, including with Carignan and Sangiovese. This needed a couple of hours to fully open, and would likely benefit from some additional near-term cellaring, the ’21 Honi is yummy, and with each sip the price tag—GBP 40 locally but I gather it can be found in the United States for around USD 48—seems perfectly acceptable to me.

L’chaim!

About Me:

By way of background, I have been drinking, writing, consulting, and speaking professionally about kosher wines and spirits for more than 20 years. For over a dozen years I wrote a weekly column on kosher wines and spirits that appeared in several Jewish publications, and my writing generally has appeared in a wide variety of both Jewish and non-Jewish print and online media. A frequent public speaker, I regularly lead tutored tastings and conduct wine and spirits education and appreciation programs. Those interested in contacting me for articles or events can do so at jlondon75@gmail.com.

In what seems like a lifetime ago, I also wrote an entirely unrelated slice of American history: Victory in Tripoli: How America’s War with the Barbary Pirates Established the U.S. Navy and Shaped a Nation (John Wiley & Sons, 2005).

When not focused on wines and spirits, I work in pro-Israel advocacy. Previously a longtime D.C. lobbyist, I relocated with the family to the U.K. during the COVID period and really prefer life across the pond despite the ongoing absurd and frankly uncivilized dearth of kosher Beaujolais here.