Welcome to Kosher Burgundy

The 'old world' wines of Burgundy, France are finally getting their share of sunlight in the kosher marketplace.

NOTE: A shorter version of this article was recently published in the annual Kosher Wine Guide magazine supplement of The Jewish Link of Northern and Central NJ, the Bronx, Manhattan, Westchester, and Connecticut; I am a contributing editor of that magazine.

The wines of Burgundy—classic, “old world,” elegant, and some of the most expensive available—are widely considered benchmarks for winemakers around the globe. Unfortunately, the availability of kosher Burgundy has been, at best, fitful—especially in the United States. Thankfully, there are several recent, active efforts underway to improve this situation.

The Herzog family’s Royal Wine Corp., the largest producer, importer, and exporter of kosher wine in the United States and Europe, will soon be releasing three high-end red wines from Burgundy—a Gevrey-Chambertin, Chambolle-Musigny and a Premier Cru Beaune, all 2020 vintage wines from Domaine du Château Philippe le Hardi (formerly known as Château de Santenay).

These are an addition to Royal’s current lineup of the excellent white Burgundy wine Château de Santenay, Les Bois de Lalier, Mercurey Blanc (to be rebranded with the Philippe le Hardi label in future vintage releases), their solid Chablis—also a Burgundy white—from Pascal Bouchard and Domaine Les Maronniers, and their enjoyable if simple entry-level Burgundies from Domaine Ternynck.

At KosherWine.com, the leading kosher wine internet retailer in the United States, the team recently launched their own high-end red Burgundy: the delightful René Lacarière, Gevrey-Chambertin, 2019. This is in addition to their delicious, unpretentious, entry-level red Burgundies: Grume d’Or Pinot Noir, Louis Blanc Duc de Serteil Coteaux Bourguignons and the Louis Blanc Morcantel Bourgogne.

Liquid Kosher, Andrew Breskin’s boutique and hyper-curated wine club, has rolled out a stellar lineup of high-end Burgundys from Domaine Jean-Philippe Marchand, made by arrangement with Le Groupe Moïse Taïeb, one of Europe’s top kosher wine négociants. While G.M. Taïeb has been working with Marchand for the last eight years servicing the European market, Breskin has revitalized the program, more fully partnering with Taïeb and Marchand with the 2021 vintage, in an exciting effort to really push kosher Burgundy in the American market.

These Marchand wines stand alongside Breskin’s fast-dwindling stock of kosher red Burgundies from Domaine Chantal Lescure, which has not produced a new kosher vintage since 2017, and from Domaine d’Ardhuy, which sadly abandoned its kosher program altogether after the 2015 vintage. (Both Lescure and d’Ardhuy were also Taïeb productions, for the European and British markets, which began in 2010; Breskin began importing the kosher d’Ardhuy in 2016, and the Lescure in 2017). Also in the Liquid Kosher lineup are some lovely Chablis from Dampt Frères and La Chablisienne.

There are also several lovely Burgundies from Maison Jean-Luc & Paul Aegerter starting with the 2018 vintage, made by arrangement with the high-end focused kosher négociant Les Vins IDS, imported by the Brooklyn-based M&M Importers. Also currently available are several reasonably priced—i.e., not much more money than their regular non-kosher versions—kosher Chablis, which are lovely, and an entry-level pinot noir from Vignoble Dampt, under their Dampt Frères label, made by arrangement with winemaker and négociant Vignobles David and imported by the New York-based Bradley Allan Imports. These are available through KosherWine.com, Liquid Kosher, and with limited in-store distribution, too.

What Is Burgundy?

Burgundy, or Bourgogne in French, is a province in eastern France famous for both red and white wines, it is also the name of the region, its wines, and the most basic, generic category of appellation. There is also a small but steadily growing amount of sparkling, and a tiny amount of pink wine produced there.

According to recent data from the Bureau Interprofessionnel des Vins de Bourgogne (BIVB, known in English as the “Bourgogne Wine Board”), Burgundy has 30,052 hectares, or 74,260.04 acres, under vine. In terms of production, there are currently 3,577 domaines viticoles (growers) producing wine (of whom 863 sell more than 10,000 bottles), 266 maisons de négoce (merchant houses), and 16 caves coopératives (cooperatives)

The heart of Burgundy wine is the Côte d’Or, or “Slope of Gold,” a roughly 30-mile-long escarpment—a fillet of angled land at the edge of the plain, with outstanding soil composition, recognized for producing exceptional wines as early as a millennium ago—starting just south of Dijon, stretching in the direction of Lyon. The name is often said to refer to the golden color of the vineyard leaves in autumn, though invariably folks joke that the name alludes to the prices the wines fetch at market. A more compelling tradition has it that the name is simply a contraction of Côte d’Orient, “eastern-facing slope”—referencing that the slope of the land is to the east, allowing the vineyards to maximize sun exposure.

Burgundy wine is grown across five primary viticultural areas. From north to south, these are: Chablis, Côte de Nuits (the northern half of the Côte d’Or); Côte de Beaune (the southern half of the Côte d’Or), Côte Chalonnaise; and Mâconnais.

SIDEBAR: Where is Beaujolais?

In terms of government administration, the province of Burgundy technically includes part of Beaujolais, located immediately to the south of Mâconnais—and so there are some who naturally consider the Beaujolais wine region as yet another part of greater Burgundy. It is not. Beaujolais has its own history, soil types, topography, climate, grape varieties, winemaking styles and personalities. The difference between the wines sold as Burgundy and those as Beaujolais are as great as chalk and cheese. Further, Beaujolais is mostly in the Rhône département, and so Burgundians consider Beaujolais wines as les vins du Rhône. The general convention, followed here, is to consider Beaujolais—which I adore!—as its own thing entirely.

The sheer weight of all this detail—and this is but a brief thumbnail sketch—hints at why Burgundy is considered so complex a wine region. On the plus side, Burgundy has one of the world’s least complicated range of grape varieties permitted in its vineyards, and the best wines of Burgundy are exclusively made from only two different grapes: Pinot Noir for reds and Chardonnay for whites.

According to BIVB, chardonnay accounts for 51% of the land under vine in Burgundy, while Pinot Noir accounts for 39.5%. The only other wine grapes cultivated in Burgundy are the white wine grape Aligoté, which accounts for 6% of Burgundy’s land under vine, the red wine Gamay grape, most famous in nearby Beaujolais, accounts for 2.5%, while the remaining 1% is made up of the red grape César, and the white grapes Pinot Blanc, Sauvignon Blanc, Pinot Gris/Pinot Beurot, Sacy and Melon de Bourgogne.

As is typical of French wines, however, the bottles rarely specify the grape variety, showcasing instead the geographic location where the wine came from.

Burgundy Is All About Terroir

This geography focus is due to the somewhat romantic but thoroughly French belief that the natural character and taste of a wine is derived largely from where the grapes are cultivated (and the wine is made, broadly in accord with traditional methods). At the core of this doctrine is the much-debated notion of what the French call terroir, which very loosely translates as “a sense of place.”

More than any other wine-growing region in France, Burgundy has enthroned the primacy of place. Burgundy is where every minute geographic nuance matters, where the whole theory of terroir is explored with the utmost intricacy and devotion. “Burgundy,” as the wine writer Matt Kramer succinctly put it, “is all about the sanctity of the land, not the brand.”

The term terroir conceptually refers to a holistic combination of such natural localized interactive factors as soil composition, topography (mostly in terms of exposure to sun and water drainage) and climate (from macroclimate down to microclimate).

The big idea is that all these factors combined confer each individual parcel of vine-growing land its own unique terroir, which is reflected in its wines from vintage to vintage. From this idea, in turn, it is deduced that every small plot—and in general terms every region—may have distinctive characteristics that are conveyed into their resulting wines and that are not subject to precise replication elsewhere. Simply put, terroir is said to be the reason why pinot noir from Burgundy tastes different than Pinot Noir from, say, Oregon, California or Israel.

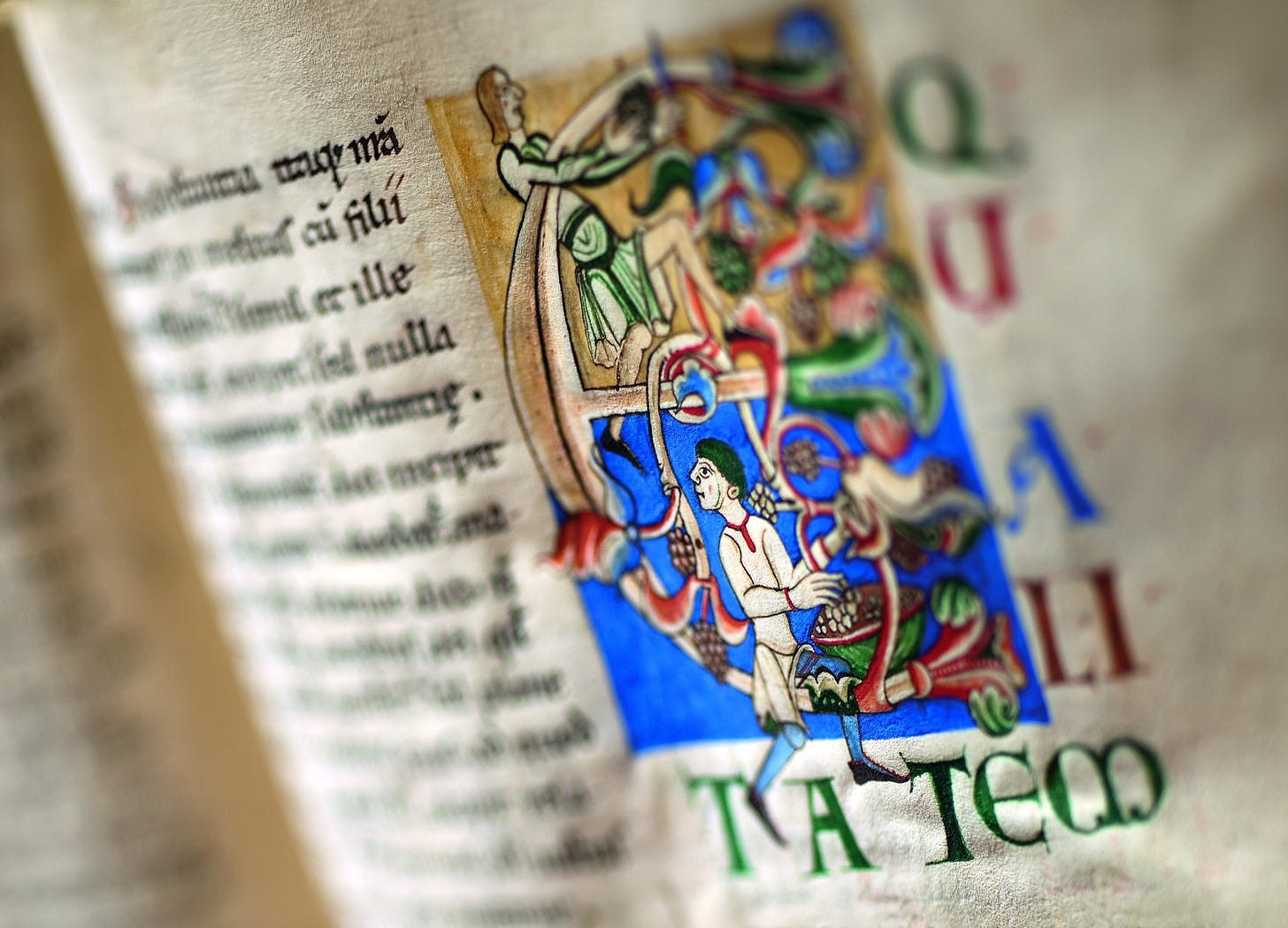

While Burgundy’s vineyards were not officially classified until the 20th century, the Christian monks of medieval France began painstakingly cultivating and identifying Burgundy’s vineyards based on the distinctive qualities each parcel transmitted to the resulting wines. Their religious devotion to cultivating the vine, it is said, laid the foundation of modern Burgundy wine.

This fixation on terroir is largely the conceptual basis upon which France’s regional classifications of vineyards have been established. This system of classification is known as the appellation d’origine contrôlée or AOC, meaning “controlled designation of origin,” and is governed by the Institut National de l’Origine et de la Qualité (INAO), a branch of the French Ministry of Agriculture.

The AOC is a form of certification meant to guarantee the characteristics of a wine in terms of the terroir where the grapes were grown; the way it is made, in broad terms; and, as the BIVB’s website puts it, “local viticultural savoir-faire, born from traditional methods that have been improved over time.”

The idea is straightforward: Every wine comes from somewhere, and if that specific somewhere is a named location that has over time developed a good reputation for consistent quality, then claiming a connection to that location—that specific geographic somewhere, if you will—takes on greater commercial value. From this vantage point, the price and perceived quality potential of a wine may be said to depend on the quality and prestige of the vineyard it comes from. The AOC was established to recognize, define, designate, rank, protect and regulate the reputations of these vineyards.

Burgundy’s vineyards have been ranked according to four levels of quality. From top to bottom, these are: Grand Cru (“great growth,” these are the very best), Premier Cru or 1er Cru (literally “first growth,” just one notch down), Village (another notch down), and Regional (the bottom tier).

In a sense, this is just a fussy way of describing an especially prized real estate market: The most exclusive addresses are thought the best, and so cost the most. So, the wines from the best vineyard sites are thought to have the best quality potential and are the most in demand, and so also the most expensive. The relationship is a simple inversion: As potential quality goes up, quantity goes down; and as availability goes down, prices go up.

Unfortunately, the Burgundy wine region map in all its minute detail is one of the most complicated in the world. Each of Burgundy’s 33 Grand Cru—32 of which are in the Côte d’Or—has its own distinct appellation. There are 684 vineyards with Premier Cru ranking. There are 43 Village appellations—theoretically a statement on each commune’s terroir, such that, for example, a consumer should be able to taste the wine and say, with conviction, this is a Morey-St-Denis and that is a Chambolle-Musigny; this is Chassagne and that is Puligny, and so on. The Regional appellations have, mercifully, been simplified from 22 to just eight.

All this complexity has its place, of course, and the wine geeks among us relish such details. But all one really needs to appreciate Burgundy, as with all wines, is curiosity, an open mind, a capacity for personal discernment of taste, an insatiable thirst and—specifically for Burgundy, alas—deep, deep pockets.

SIDEBAR: Terroir and the Côte d’Or

The French devotion to the individual vineyards, or climat, of the Côte d’Or is seemingly boundless. The term climat refers to “a vine plot, with its own microclimate and specific geological conditions, which has been carefully marked out and named over the centuries,” and the climats of the Côte d’Or are, since 2015, part of the UNESCO World Heritage list. These are essentially the vineyard names in Burgundy that have emerged out of the mix of 2,000 years of history, hard viticultural work and wine tasting appreciation. At any rate, there are a whopping 1,247 of these climat registered with UNESCO, stretching out in a thin ribbon from Dijon down to Santenay, south of Beaune.

Kosher Burgundy Past to Present

“Until recently, Burgundy has been really underrepresented in the kosher wine market,” Dovid Riven, president of KosherWine.com, noted in our phone call. Indeed, he said, “it had sort of disappeared from the U.S. market over the years,” though it was still available in limited quantities elsewhere. “I don’t know why it left the U.S., but it did.”

Yet 20-30 years ago, there were several seemingly solid efforts afoot trying to propel kosher Burgundy into a more permanent position in the American market.

Indeed, as far back as 1990, as Yoni Taïeb, directeur général of G.M. Taïeb, told me, his company began producing Chablis “in order to develop a range of Burgundy demanded by our clients and partners.” They did so with the esteemed La Chablisienne cooperative, mainly for the British and Israeli market. Howard Abarbanel, one of the early pioneering kosher wine importers in the U.S., began importing Taïeb’s Chablis a couple of years later, for a little while. Taïeb’s kosher production of Chablis has continued, of course, though none of it was reaching the U.S. until 2021—as Liquid Kosher is now importing the most recent vintage (2018) of the La Chablisienne Chablis Premier Cru.

Another of the better early kosher Burgundy options was from négociant Les Vins Mayer Halpern (alas, no longer in business), which produced several delicious red and white Burgundies with Domaine Gaston et Pierre Ravaut. Though perhaps the biggest splash came from the négociant Roberto Cohen (alas, also no longer in the wine trade), who produced a wide array of kosher Burgundies in the early 2000s under his own label with Domaine Jean-Philippe Marchand, among others; his wines were imported to the U.S. by Abarbanel. These Roberto Cohen wines represented a major category-wide push, and some of these—not all, alas—were really lovely. The pricing, however, was widely thought to be misaligned with the kosher market at that time.

It wasn’t long before the Roberto Cohen line caused some tumult between consumers and retailers, and eventually Cohen’s wines jumped from Abarbanel to the Royal Wine Corp.’s portfolio, before being completely discontinued in the U.S. While Cohen carried on his own-label production with Marchand for around 10 years, servicing Europe and occasionally Israel, his wines never returned to the U.S., and it all ended when Cohen left the trade around 2014. Thankfully, G.M. Taïeb picked up with Marchand a couple of years later, releasing kosher wines under Marchand’s own brand (and now part of the Liquid Kosher portfolio).

“I had greatly enjoyed making kosher Burgundy for Cohen,” Marchand told me, “So I was very pleased when Taïeb contacted me to make kosher with them—Mr. Taïeb has a very high reputation; it’s been a marvelous experience.”

“I set aside part of my [second] winery in Morey-St-Denis just for kosher vinification,” Marchand explained. “I told Mr. Taïeb, ‘This will be just for you, for kosher’ because, as you know, nobody else can be involved during kosher vinification. My own method [approach] to vinification is very similar to kosher; I prefer to use more and more a clean, natural approach, nothing artificial.”

There were other significant kosher Burgundy efforts, too. Royal Wine imported the generally excellent kosher Chablis produced with Pascal Bouchard by arrangement with the esteemed négociant Selection Bokobsa SIEVA—an effort that remains ongoing; 2018 is the most recent vintage. (A Tunisian-French family and company, Bokobsa has been producing kosher wine in France since 1966, they also distribute Royal’s wine in France.) More recently, Royal has partnered with Laurent and Marie-Noëlle Ternynck of Domaine de Mauperthuis, producing some solid Chablis under the Les Marrioners label, and an enjoyable regional entry-level red and white under the Domaine Ternynck label—the forthcoming 2020 vintage will, I am informed, see a boost in quality.

Perhaps most notably of all these earlier Burgundy efforts, however, are those from the always great Pierre Miodownick. Prior to his joining the Herzog family’s Royal Wine Corp. as its first chief European winemaker in 1988, Miodownick made several lovely and long-lived kosher Burgundies, including a Gevrey-Chambertin and a Meursault under the Anselme Desler label. Royal had the foresight to not only import and distribute these wines, but crucially also to hire Miodownick. (He, of course, impressed by producing a lot more than just these wines.)

After joining Royal full-time, Miodownick continued his Burgundy efforts—along with his far more significant and category-expanding Bordeaux efforts—as part of Royal’s broader European kosher wine program. His Burgundy wines under Royal included several kosher-runs with François Labet—such as Labet’s much vaunted Chateau de La Tour Clos de Vougeot, an impeccable Grand Cru.

“Part of the problem with these early [high-end Burgundy] wines,” explained Menahem Israelievitch, Royal’s current chief European winemaker—he succeeded Miodownick, his mentor, in the chief winemaker role in 2009— “was that the American market was simply not yet ready for Burgundy; it was too early.”

Further, Israelievitch noted, “Royal did large productions [of these high-end Burgundy wines], and they did several vintages in a row,” so they essentially over-produced. “They lost a lot of money,” he noted somewhat sheepishly, “and so they totally abandoned the effort then … we had many bottles sitting unsold in the warehouse for too long.”

When Royal suspended its kosher Burgundy efforts, the market for them in America seemingly dried right up. In some instances, like with Roberto Cohen’s label, the wines were still being produced, only they were no longer finding their way here to the U.S. Kosher consumers could see online what was available overseas, however, and those with deep pockets or who traveled to Europe frequently were able to keep tabs on developments abroad.

Kosher runs of Burgundy since the early 1990s were simply never really intended to reach the American market. Yoni Taïeb, of G.M. Taïeb, informed me that following their successful kosher Chablis productions (which Abarbanel did import here for a time), they began producing red Burgundy as early as 1994. To facilitate this effort, they established a kosher production team in Lyon, just south of Burgundy. “Without the presence of the shomrim team [kashrut agency processors/supervisors] based in Lyon—just one hour from the properties, which meant they could be very responsive to production needs,” he explained, “it would have been too difficult to produce great kosher Burgundies.”

This Taïeb team produced, from 1994 to the early 2000s, kosher runs of white and red “prestigious Crus” in Burgundy—all “in small quantities of just a few hundred bottles per appellation—given the rarity and the significant world demand, this was all we could persuade the properties into making kosher.” This was the “first small production of Clos de Vougeot Grand Cru, Santenay, Puligny Montrachet red and white, Volnay, Pommard, and Meursault.” None of this ever came to the U.S.

Everything they produced “quickly sold out, mainly on the French and British markets.” Eventually market forces and shifting weather patterns meant that the various producers’ grapes became both more limited and more valuable, and eventually Taïeb’s larger Burgundy program was suspended. They stuck with their Chablis, however, and eventually resumed production of red Burgundy with Domaines Lescure and d’Ardhuy in 2010.

Most recently, MesVinsCacher.com, a prominent European online kosher wine retailer, worked with Domaine Charles Père & Fille to produce several 2020 vintage wines entirely for the European market. (The Domaine assures me that future kosher vintages for MesVinsCacher are planned as well.) Likewise, Honest Grapes, a U.K. fine wine retailer, has a stunning en primeur kosher Burgundy program underway with the esteemed Domaine de Montille for eight different wines from the 2020 and 2021 vintages, five of which are Premier Cru. (They have a similar ongoing exclusive kosher program with JCP Maltus in Saint-Émilion, Bordeaux.) These, too, are not at all aimed at the American market (though Madeb’s M&M Importers has since arranged to eventually import a little of this, if any remains available).

“The First Duty of Wine Is to Be Red, the Second Is to Be a Burgundy” — Harry Waugh

“We wanted to bring high-quality red Burgundy back to the kosher market in America,” KosherWine.com’s Dovid Riven told me. “So, we started to call our contacts in France and explore the possibilities.”

At the time they first began the project “there wasn’t any kosher red Burgundy widely available in the U.S.,” so they perceived a real need. After all, he added, “quality red Burgundy is truly something that should be widely available to the kosher consumer—when red Bordeaux is great, it’s really great, but when red Burgundy is great—it is sublime.”

It has often been said among wine aficionados that on the journey to wine understanding, all roads eventually lead to Burgundy (though, arguably, the same might be said of Barolo and Barbaresco). Burgundy is the birthplace of both pinot noir and chardonnay, the two grapes from which all high-end Burgundy wine is produced, and so draws the attention and affection of wine lovers the world over.

Pinot noir is one of the world’s great red wine grapes. Wine writer Andrew Jefford once aptly noted that, “Pinot noir is the poet among grape varieties. Long flowing locks; flashing eyes; exasperating and sometimes childish behavior redeemed by occasional brilliance. No grape has broken more winemaking hearts than this one.”

Similarly, if the wine grape world can be said to have celebrities, then chardonnay is perhaps the biggest of them all—with legions of fans and an army of detractors, and yet is recognized by all who have even just passing familiarity with wine. As the wine writer Jancis Robinson, MW, once put it, “There is a reason why chardonnay is the most widely distributed white wine grape in the world. Its appeal is universal.”

Many consider both grapes to perform their very best in Burgundy—so a focus or refocus on Burgundy for the kosher market should not come as too much of a surprise.

For Andrew Breskin of Liquid Kosher, the appeal of Burgundy has more of the familiar twinkle-in-the-eye romance of a smitten wine aficionado. “I think that Burgundy is the highest expression of red wine for time and place,” he explained.

“As you drink other red wines and get a sense of how vintage and vineyard affect the taste of the wine,” said Breskin,

you go to a place like Burgundy and the differences are so dramatic and so exaggerated between different vineyards that are only separated by a very short distance … that it just causes you to want to learn more, and want to experience more, and taste more, to really understand the region and what about it causes such maddening and exciting distinctions in the wine and in the most delicious way possible.

For better or worse, however, “Burgundy has become very complicated [on the production side],” Menahem Israelievitch observed, “even in the non-kosher market.”

“The quantities being produced [there],” Israelievitch explained, “are really, really very small, and have remained smaller than expected every year for the past five years.”

“Demand has outstripped supply by ever-larger amounts,” Riven noted, “and the already limited supply has been further squeezed by low-yielding growing seasons.”

SIDEBAR: Burgundy and Climate Change

Burgundy lends itself to obsession, and easily one of the biggest at the moment—amongst growers, négociants, importers, collectors, and critics—is the impact of climate change. Burgundy is, after all, one of the preeminent and classic cool-climate production areas.

According to the BIVB, the average temperature in Burgundy has increased one degree Celsius since 1987. This is widely understood as the effects of climate change. In Burgundy, however, it was considered relatively beneficial until the last few years.

Over that period, compared against the previous two decades, bud flowering and grape harvesting have been on average two weeks earlier. While an earlier growing season increases the vulnerability of tender buds to potential spring frosts, the red grapes have enjoyed more reliable maturation and better quality overall. Hence the urgency to adapt to climate change in Burgundy has been perceived to be lacking. “2018 marks a turning point,” noted Jasper Morris, MW, in his tome Inside Burgundy, “reinforced by the two subsequent vintages.” Burgundians are actively exploring options for adapting how they do what they do.

As Hugh Johnson astutely observes in the 2021 edition of his annual Hugh Johnson’s Pocket Wine Book,

all farmers will be affected, but … wine-growers are the most sensitive, the most finely poised. The great wines of the world are the result of fine equations of land, weather and vines chosen to ripen grapes at the right speed and the right moment. Because the equation is precise it is inevitably marginal, and marginal means fragile.

“The shocking beauty of wine is testament to nature’s grandeur and fragility,” Andrew Jefford noted in his Decanter magazine column of January 1, 2020.

Winemakers steward wine into being, but it’s nature that undertakes the work of creation, and leaves wine palpably engraved by place, and by the faintest of seasonal pulses.

For now, at least, there is no clear widespread programmatic response, so the obsession and its furrowed-brow hand-wringing continues apace.

“Increasingly,” lamented Israelievitch, “[Burgundy] producers are having to allocate even their basic Bourgogne appellation wines, not just their higher-end wine. There simply isn’t enough wine being produced to go around.”

As Jean-Philippe Marchand, representing the seventh generation of his family in Burgundy wine, put it to me,

“Production has been going down, especially with the terrible frost of last April, and world demand is going up, and so the price is going up too … it is the first time in my life to see a situation like this—we have no wine available, and the price is quite expensive.”

“The Burgundy market has become similar to high-end Bordeaux,” mused Dovid Riven, “in that it is particularly expensive to dabble in—the producers don’t need to do the kosher business; they can basically sell as much as they can produce already.”

Riven said their project was years in the making: “For us, it finally all came together for the harvest of 2019, so we jumped on it.”

“As it happens,” he laughed,

we weren’t the only ones then who decided to bring kosher quality red Burgundy to the American market—but this is a good thing overall for the kosher consumer here; the more the merrier!

Instead of our project being one of a kind, it became one of several, but probably the most widely available of what’s out there.

Riven is perfectly fine with that. “Our focus is providing for our customers, first and foremost,” he said. “If, or as, others build out the kosher Burgundy space in the market, we’ll adapt our activities accordingly. The kosher market has plenty of room for growth.”

For Israelievitch, returning to Burgundy appealed on several levels. For one, it was a return to his earliest fully professional days with wine. Although he grew up in Paris and spent years in yeshiva in Israel, invariably he returned to France at grape harvest time each year. “A friend suggested I join him as a mashgiach; I was 16; I found it very interesting,” he explained, “and so every year during my vacation I did this job.”

After completing his yeshiva education in 1999, Israelievitch returned to wine more professionally. He was hired by Royal to manage the vinification for the Loire Valley year round, “and I looked after all the wines in the Loire and also in Burgundy.” He and his team oversaw kosher production, under Miodownick, at three wineries in the Loire and four in Burgundy—including the kosher Grand Cru wines made with François Labet at his Château de La Tour Clos de Vougeot.

Israelievitch clearly has all the telltale signs of a French winemaker with an itch that only Bourgogne can fully scratch. Israelievitch elaborated,

There is a certain lovely simplicity to producing wine in Burgundy because you work with the grapes from the small vineyard, trying to simply allow them to speak, and showcase what they have to offer of themselves. The volume is less, so the work is faster—but it is generally more expensive because of the small quantities, too. Really elegant, refined, wonderful wines.

“Once I thought the market was ready again for Burgundy,” he said, “I began urging the Herzogs … I drove them crazy, and it really wasn’t easy, and took a lot of time to convince them to try Burgundy again.” Thankfully, he persisted and eventually prevailed.

Having been given the green light, he said,

I looked for a Domaine in Burgundy with whom we could really work; I did not want to work through a négociant; I wanted to have something of high quality that we would control … and I didn’t want to have to deal with any potential compromises.

The current plan, is to expand this every year, to not just keep production going on the wines that are working out well, but also to include additional appellations on a small scale. Last year we launched the Mercurey, and now we will launch these reds.

“The idea is to build a real and sustained Burgundy portfolio,” he said excitedly,

but to do so in concert with what the market will bear. I want to do this right and build it out properly, and to avoid the mistakes of the past.

About me:

By way of background, I have been drinking, writing, consulting, and speaking professionally about kosher wines and spirits for more than 20 years. For over a dozen years I wrote a weekly column on kosher wines and spirits that appeared in several Jewish publications, and my writing generally has appeared in a wide variety of both Jewish and non-Jewish print and online media. A frequent public speaker, I regularly lead tutored tastings and conduct wine and spirits education and appreciation programs. Those interested in contacting me for articles or events can do so at jlondon75@gmail.com.

In what seems like a lifetime ago, I also wrote an entirely unrelated slice of American history: Victory in Tripoli: How America’s War with the Barbary Pirates Established the U.S. Navy and Shaped a Nation (John Wiley & Sons, 2005).

These days I divide my time between London (UK), and Washington, DC.