The Jewish holiday of Pesach (פסח), better known in English as Passover, is just around the corner, and so many Jewish people will give at least a moment’s thought to selecting appropriate wines for the holiday.

Pesach starts on the evening of the 15th day of Nisan [ניסן] in the Jewish calendar, which generally falls around late March or early April. The holiday lasts for seven days in the Land of Israel, and eight days in the Diaspora (outside of Israel). Pesach 2022 begins on Friday night, 15 April, and continues in the Diaspora through Saturday evening, 23 April (in Israel it ends on Friday evening, 22 April; see here for more details on the holiday itself).

Although there are plenty of other priorities for those prepping for Pesach, making sure one has appropriate wines on hand remains very important. Afterall, wine is an essential component to religious Jewish life in general, and even more so for the Pesach holiday.

For starters, there is an obligation for Jewish people to each drink arba kosot (ארבע כוסות), or four cups of wine, during the Pesach seder (סדר), the ritual banquet celebrating, commemorating, and retelling the story of the Exodus—of God taking the Jewish people out of Egyptian bondage over 3,000 years ago. In the Diaspora, Jews will have Pesach seder on the first two nights, so think of it as eight cups, rather than four, per person in terms of planning. On top of this, Jews who choose to religiously observe all the days of the holiday will also need wine to commence each holiday meal—as is done every Sabbath, and festival. By any reckoning, that’s a fair amount of wine.

Not surprisingly, the kosher wine industry considers Pesach to be their busiest season. Gabriel Geller, Director of Public Relations and Advertising and Manager of Wine Education with the Herzog family’s Royal Wine Corp., the largest producer, importer, and exporter of kosher wine in the United States and Europe, says that the Passover season accounts for 40-45% of annual sales. (He says that Rosh Hashanah/Sukkot—roughly September/October—is about 30%, “and the remaining 25-30% is spread out throughout the rest of the year.”)

Why wine? A general grasp of how wine is incorporated into the life of a traditional Jew will help make clear the pride of place wine has been given on Pesach.

The Role of Wine in Judaism

Wine is accorded special status in Jewish tradition, and is considered in turns both powerful and sublime, but with obvious inherent potential dangers too.

As I’ve noted previously, Judaism despises drunkenness. The Talmud and Midrashim—collections of rabbinic discussions, lore, and homilies from the late Talmudic period—are rife with discussions that highlight the problems associated with immoderate wine imbibing (see, for example, Ketubot 65a; Megillah 12b; Niddah 16b; Eiruvin 64a; Sanhedrin 70a-b; Midrash Tanchuma Noach 13; Vayikra Rabba 12:1; Bamidbar Rabbah 10:8). Similarly, the ethical writings, philosophy, and homiletical literature of countless distinguished rabbis give ample voice to the Jewish view on the dangers of intoxication and immoderate consumption (for a contemporary and very fine example of the genre see Dovid Page’s 2022 L’Chaim! The Torah View on Wine, Alcohol, and Intoxicants, also available in Hebrew as Sodo Shel Eitz Hada'as).

There are, of course, also instances of the Rabbinic Sages praising the consumption of wine. For example, “Rabbi Chanina said: Whoever is appeased by his wine, has in him the mind-set of his Creator,” “Rabbi Chiyya observed: Anyone who remains clear of mind after wine possesses the characteristics of the Seventy Elders,” “Rabbi Chanin bar Pappa said: Anyone in whose house wine does not flow like water is not yet included in the Torah’s blessing,” and “Rabbi Ilai said: By three things may a person’s [true character] be determined: By his cup [of wine], by his wallet and by his anger; and some say: By his laughter also” (Eiruvin 65a-b). Perhaps most profoundly of all,

Rabbi Yehuda ben Beteira says: When the Temple is standing, rejoicing is only through meat…Now that the Temple is not standing, there is no joy without wine” (Pesachim 109a).

And so we see that, concerns over alcohol-induced impropriety aside, wine was in fact given a central role in Jewish life and remains an essential component of Jewish religious practice.

On Jewish festivals, for example, we are enjoined to be joyous, and explicitly to do so with wine. For, as the Psalmist writes (104:15), “Wine brings joy to the heart of man.” Likewise, in Ecclesiastes it is noted (10:19) that, “wine gladdens life.” Indeed.

With so much joy and gladness, it’s no wonder that the Talmud (Pesachim 109a) writes:

The Sages taught: A man is obligated to gladden his children and the members of his household on a Festival, as it is stated: “And you shall rejoice on your Festival” [Deuteronomy 16:14]. With what should one make them rejoice? With wine.

In recognition of the inherent special status of wine, the Rabbinic Sages of the Talmudic era gave wine—and, indeed, also grape juice—its own distinctive b’racha [ברכה], blessing, borei p’ri hagafen (בורא פרי הגפן) “Creator of the fruit of the vine,” rather than the standard b’racha recited for all other beverages —shehakol nihiyeh bidvaro (שהכל נהיה בדברו), “that all came into being through His words.”

As Rabbi Binyamin Forst writes in his 1989 book, The Laws of B’rachos (B’rachos is simply the transliteration of the Ashkenazi Jewish pronunciation of B’rachot [ברכות], blessings):

Grape wine has special status in the world of b’rachos. It is the only food that both physically satisfies and brings joy to the spirit…Furthermore, wine represents the essence of the grape. The grape was created for its juice. One plants a vine not for its grapes but for the wine (pg. 312).

Wine is the premier liquid drink. All other liquids are considered secondary to wine. Thus, the b’racha recited over wine covers all other liquid drinks that are present on the table when the b’racha is recited (page 323).

NOTE ON BRACHOT:

The practice of reciting of b’rachot was instituted by the Rabbinic Sages of the Talmudic period, so that we will “constantly remember the Creator, and be in awe of Him” (Rambam, Mishneh Torah, Sefer Ahavah, Hilchot B’rachot 1:4). The Talmud is crystal clear on the matter (Brachot 35a-b):

One is forbidden to derive benefit from this world without [first making] a b’racha…and anyone who has benefited from this world without [first making] a b’racha…has abused…that which has been consecrated to the heavens, as it is stated: “The earth is the Lord’s, and the fullness thereof…” (Psalms 24:1).

There are three basic types of b’rachot in Judaism:

Birchot HaNehenin [ברכות הנהנין], Blessings of Benefit: The type that broadcasts that we imminently plan to benefit by using something that is rightfully His, such as food.

Birchot HaMitzvot [ברכות המצות], Blessings over Commandments: The type that declares that we intend to fulfill a mitzvah [מצוה], or commandment.

Birchot HaShevach [ברכות השבח], Blessings of Praise: The type that acknowledges the authority and power of God, usually in response to some moment or experience that bespeaks His all-encompassing majesty, such as seeing or encountering a natural wonder, or that recognizes some fundamental aspect of our daily existence that we might otherwise take for granted, such as waking-up from sleep, our ability to see, our ability to be ambulatory, the clothes on our backs, our liberty, our ability to use the washroom, etc.

American culture may have Judeo-Christian roots, but it isn’t the Jewish component that is dominant. The religious attitude and disposition to the simple act of eating is illustrative of the distinction. Jews do not give thanks to the Almighty until after we have eaten, since any number of things might happen between our b’racha and the activity, and we strive never to make a b’racha in vain. Instead, the Jewish approach is to bless and praise Him for creating the food we intend to consume, and then bless and praise Him in thanks after we have consumed it, and so we tailor these b’rachot with a great deal of specificity—at least as compared to such non-Jewish benedictions as “For what we are about to receive,” or “Bless us, O Lord, and these Thy gifts”, or even “Give us this day our daily bread.”

Thus, different categories of food require different types of b’rachot. Wine and grape juice have their own b’racha, as mentioned above. Bread has one b’racha, while there is a different b’racha for grain products that properly fit into a category other than bread due to their ingredients or preparation. There is another b’racha for fruits and vegetables that grow from the ground, and a different b’racha for fruit that grows on trees. There is yet another catchall b’racha for everything else, meat, fish, and every liquid that isn’t grape based.

These b’rachot exist in a hierarchy—whereby some b’rachot should be said before others if multiple food items will be eaten at one siting, and the b’racha for bread obviates the need to make additional b’rachot over other foods of that meal (though before eating bread, one first washes their hands, an act which requires a b’racha of its own). Upon completion of the meal or snack, we bless God accordingly. All of these b’rachot were established by the Sages with specific Hebrew formulations and are recited as per their specific wording.

Because of this special role accorded to wine, the Sages attached the kos shel b’racha (כוס של ברכה), [wine] cup of blessing, to many religious activities and obligations.

These activities and obligations include, kiddush (קידוש; sanctification), and havdalah (הבדלה; separation), to sanctify and demarcate the beginning and end of each Shabbat (שבת), the weekly Sabbath. Likewise, we make kiddush before the formal meals of the Yomim tovim (ימים טובים; literally ‘good days’), also known as Chaggim (חגים; festivals).

[Yomim Tovim and Chaggim refer to any of the six biblically mandated holidays outside of the weekly Shabbat, which also share Shabbat-like prohibitions (with the exception of some activities related to preparing foods/meals). These holidays are: 1. Rosh Hashanah (start of the year), 2. Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement), 3. Sukkot (Booths/Tabernacles), 4. Shemini Atzeret (Eight [day] of Assembly), 5. Pesach (Passover), and 6. Shavuot (weeks).]

Jewish wedding ceremonies also involve wine. First at the erusin (אירוסין) or betrothal, also known as the kiddushin (קידושין) or sanctified, this is when the groom betroths his bride—in which they become sanctified to each other— by giving her a ring at the wedding ceremony, after which the officiant recites a blessing over wine. Secondly, wine is essential at the sheva b’rachot (שבע ברכות) or seven blessings, said under the chuppah (חֻפָּה) or [wedding] canopy, and also when these same b’rachot are recited at each of the festive meals the week after the marriage ceremony.

Wine is also part of the brit milah (ברית מילה), or circumcision, initiating baby boys into the Jewish fold—both through the b’rachot said with the kos shel b’racha, and a little of the wine is also given to the [eight-day-old] lad to calm and sooth him. And when the opportunity presents itself, wine is also used during the ceremony of the pidyon haben (פדיון הבן), or redemption of the firstborn son.

Finally, wine is also used when the requisite quorum is present for the birkat hamazon (ברכת המזון), or thanksgiving blessings recited at the end of a meal that involved bread.

Going back even further into Jewish history, wine libations accompanied most of the animal sacrifices (see also Bamidbar 15:1-16; 28:7-31) back in the days of the Beit HaMikdash (בית המקדש), Holy Temple in ancient Jerusalem. The Temple service was the primary form of Jewish worship, and indeed, the Temple was both the bedrock and backbone of all Jewish religious life—until the Roman conquest and destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE. Despite its disappearance two thousand years ago, the Holy Temple—and the messianic promise of redemption, return, the rebuilding of the Holy Temple, and the return of the Temple service—remains a constant and ever-present trope in daily Jewish prayer.

The Kiddush

The Kiddush prayer is a fundamental part of Jewish life, and so is also a key to understanding the Jewish use of wine.

The importance of Shabbat to Jewish life simply cannot be overstated. As Rabbi Moshe ben Nachman (1194–1270), the medieval Catalonian Jewish scholar—often referred to by Jewish historians as Nachmanides and more widely known to religious Jews by the Hebrew acronym of his name, Ramban (רמב״ן)—explains:

…the Rabbis, of blessed memory, have said that Shabbat is equal in importance to all the commandments in the Torah…because on Shabbat we testify to all the fundamentals of the faith — creation, providence, and prophecy.

The weekly use of wine to begin and end Shabbat is accorded tremendous importance in Jewish law. As the Talmud (Pesachim 106a) notes:

The Sages taught [regarding the verse] ‘Remember the day of Shabbat to sanctify it’—Remember it over wine.

That verse is the fourth of the Ten Commandments (Exodus 20:8): “Zachor (זכור; Remember) the day of Shabbat, l’kadsho (לקדשו; to sanctify it),” and then when repeated in Deuteronomy (5:12), the commandment is given as, “Shamor (שמור; Observe or Safeguard) the day of Shabbat, l’kadsho.” The use of both Zachor and Shamor are understood to mean that proper observance of Shabbat requires a twofold mission.

Zachor is a positive command to remember Shabbat, to make us recognize the importance and meaning of Shabbat both on the day, from beginning to end, but then also on every other day of the week. Thus, normative Jewish life is anchored around the Shabbat—every day of the week is referred to in relation to its proximity to Shabbat (Sunday is the “first day of the Shabbat,” Monday is the “second day of the Shabbat,” and so on).

Shamor is a negative command to refrain from work and related mundane activities—anything that would diminish the holiness of the day—to observe and safeguard the Shabbat as a day of rest.

The word l’kadsho can be understood as both “to sanctify it,” and also “to keep it holy.” We are therefore instructed and required by Jewish law to sanctify the Shabbat through a verbal declaration, at both its beginning, through the kiddush prayer, and conclusion, through the havdalah prayer. To enhance the occasion, the Rabbinic Sages decreed that both prayers should be recited over a cup of wine. Thus, the Sefer HaChinuch (ספר החינוך; Book of Education), a popular but anonymous 13th century work that details the 613 Biblical Commandments, and seeks to explain the reasons for them, writes:

The idea of this mitzvah is in order to awaken ourselves by means of action to an awareness of the greatness of the day, to plant within us faith in the Creation of the world, “For in six days did God create the world…

That is why we are commanded to recite Kiddush with wine, for the nature of a person is aroused when he feasts and is happy.”

Wine & Joy

While the Bible is clear on wine’s joy-inducing properties to humanity, the idea is pushed further still: “And the grapevine said to them, ‘I have withheld my wine, that brings joy to God and men’” (Judges 9:13).

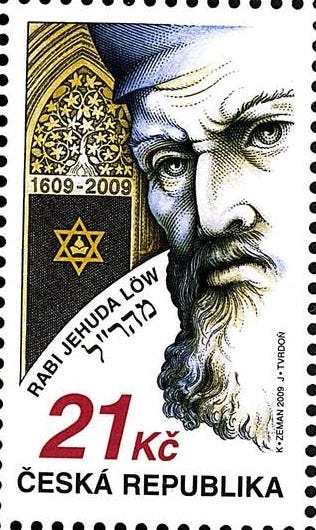

From this verse, the 16th century sage Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel—better known as the Maharal of Prague (מהר״ל; from the Hebrew acronym of “Moreinu ha-Rav Loew,” meaning “Our Teacher, Rabbi Loew”)— explained that, “wine is not part of this world, for wine has a Divine aspect to it” since it gladdens God as well as mankind. As he elaborated:

This can be understood by noting that wine comes from the inner part of a grape, which is hidden. This indicates that wine comes from a hidden place [and has a spiritual aspect] that is not part of the visible world…All things that are powerful and possess a Divine aspect can be used correctly to acquire a spiritual ascent; however, one who uses them incorrectly acquires a form of death... When one drinks wine correctly, he is made sharp and given Divine wisdom. But if one drinks to fulfill his base desires, and becomes drunk, he brings upon himself death and mourning.

Examining the same verse in the book of Judges, Rabbi Achai Gaon, the 8th-century author of the oldest known post-Talmud collection of homilies, addresses the big underlying question: “We can understand that wine brings joy to men, who drink it, but how does it bring joy to God?”

His answer: Wine fills man’s heart with joy, leading him to sing praises to the Lord, which in turn brings Him gladness. This is also why the Levites only began to sing their praises during the wine libation in the Temple.

Four Cups of Wine

This reasoning of Rabbi Achai Gaon helps us better understand the Pesach seder’s four cups of wine, as the purpose of the entire exercise of the Pesach seder is not only to retell the story of the Exodus, but also to rejoice and sing praises to God. We do so while holding a cup of wine, a kos shel b’racha, just as the Levites sang in the Temple during the wine libation, brought as an offering on the altar.

As Rabbi Mordechai Yoffe (c. 1530 –1612) expounded, this is, in fact, precisely why the Sages instituted the kos shel b’racha accompaniment to so much of Jewish life. As he put it,

For it is honorable and praiseworthy for the Blessed One’s praise and blessing to be said with a cup of wine in hand. This is as the verse says (Psalms 116:13): ‘I lift up the cup of salvations, and I call out in the name of God.’

Wine is even more important to the Passover Seder, as the Talmud states:

The Sages taught: All are obligated [to drink] these four cups – men, women, and children (Pesachim 108b).

That every Jew shares this duty to rejoice and sing praises to God over the four cups of the seder is rooted in the Jewish Exodus from Egypt. As the Talmud Yerushalmi notes in this oft cited explanation (Pesachim 10:1):

Rabbi Yochanan said, quoting Rabbi Benayah, that they [the four cups] correspond to the four stages of redemption (Exodus 6:6-7): ‘Therefore, say to the children of Israel, ‘I am the Lord, and I will bring you out [וְהוֹצֵאתִי] from under the burdens of the Egyptians, and I will save you [וְהִצַּלְתִּי] from their enslavement, and I will redeem you [וְגָאַלְתִּי]… And I will take you [וְלָקַחְתִּי] to Me as a people’

The Talmud also explains the drinking of the four cups of wine on Pesach as a symbol of our religious freedom (Psachim 109b).

As the 12th-Century sage Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon (aka Maimonides), explains,

In each generation, one must present oneself [at the seder] as if one is personally leaving the bondage of Egypt…when one eats on the night, one must eat and drink reclining in the manner of a free person…each and every person, both men and women, must drink four cups of wine on this night…On each of these four cups, one recites a blessing of its own.

In other words, at the seder every participant is obligated to consume four cups of wine as an expression of freedom, rooted in the shared experience of being taken by God out of Egypt, saved from a life of bondage, and redeemed and ennobled through God’s revelation. And this is all so that we may seek to fulfill the promise of being a Holy Nation, ultimately in the Holy Land of Israel.

Each of the four cups is also connected with a specific aspect of the seder, each of which emphasizes exultation of God, in keeping with Achai Gaon’s explanation of the joy-inducing aspects of wine for both mankind and God.

So, as on other festival evenings, the meal begins with kiddush, praising God for choosing the People of Israel and giving them His holidays, recited with a cup of wine in hand.

Upon concluding the main narrative segment of the Haggadah (הגדה; see here for the text), the booklet by which the Pesach seder is organized and run and which provides the shared text for the proceedings, we then praise God for redeeming us from Egyptian bondage, and drink the second cup.

After the meal, having emerged from this shared relived experience at the seder—and finished fresn (פֿרעסן) the sumptuous Pesach feast—we then praise God for the food, and drain the third cup. The evening proceeds with Hallel [הלל; praise], consisting of selections from the Psalms, at the end of which we imbibe the fourth and final cup of wine.

Each of these four acts of drinking the cup of wine in its proper place and order is its own separate mitzvah that involves a distinct blessing, recited over a full cup of wine which, of course, we then consume. (Many have the custom of quickly guzzling the cup entirely so as not to risk drinking less than the required measure, for drinking less than the minimum measure risks failing in their obligation to drink the cup of wine, and thereby also reciting a b’racha in vain).

Whether or not we consume any wine during the meal itself, is a matter of personal choice, but consuming each of these four cups of wine are obligatory.

NOTE:

The classic Jewish toast לחיים, usually transliterated as l’chaim or l’chayim, means “To Life!” and is thought typically Jewish, since Judaism places great emphasis on life, and on the importance of living, and on preserving life. While its exact origins are uncertain, it seems to have very deep roots in communal practice.

More than two thousand years ago, for example, the Talmud—in order to refute concerns that such toasts might have problematic pagan origins—records an anecdote about the Talmudic sage Rabbi Akiva (roughly 70 CE to around 135 CE). “Rabbi Akiva,” the Talmud relates (Shabbat 67b), once

made a banquet for his son, and over each and every cup he brought he said: ‘Wine and life to the mouth of the Sages, wine and life to the mouth of the Sages and to the mouth of their students.’

Based on this account, the contemporary scholar Rabbi Hayim Halevy Donin, in his wonderful To Pray as a Jew, credits the practice to Rabbi Akiva.

There are various other reasons proposed as to why לחיים as a toast was so widely accepted. The Talmud (Ketubot 8b) relates, for example, that it was a widespread custom in that time to give wine to mourners sitting in bereavement—“The Sages instituted ten cups [of wine to be drunk] in the house of the mourner.” This custom, known as the “Cup of Comfort” (כוס של תנחומין), was so widespread, that elsewhere the Talmud (Eruvin 65a) records, “Rabbi Chanin said: ‘Wine was created only in order to comfort mourners [in their distress]…”

So, per the example of Rabbi Akiva, when it came to joyous occasions, expressions of gladness and joy were voiced as a sort of prayer in the hopes that drinking wine would be an extra enhancement לחיים, “for life”, rather than to continue to be a beverage of consolation grief, that is “for death.”

Likewise the Midrash Tanchuma relates that after deliberating on a capital case the judges of the Jewish court would turn for a final time to those who were sent to questions the witnesses, asking for their opinion: the judges would call out, “Attention, gentleman” (סברי מרנן), and they would respond either with “to life” (לחיים) or “to death” (למיתה). If the defendant were eventually found guilty, the condemned would be given very strong wine to diminish the pain of the execution. Thus, when consuming wine for joy and celebration, the phrase l’chaim is thought in this context to have additional joyous resonance.

Choosing Wines

Ok, still with me? I’m nearly at the wine now.

The Talmud is not entirely silent on the issue of the actual quality of wine for the seder, especially since the four cups are meant to serve as a sort of “toast” to our freedom. That said, wine in Talmudic times seems to have been something of a dark age in terms of modern notions of wine quality. Further, much confusion has emerged from Talmudic discussion about proper dilution of wine with water, and the consequent codification of such dilution in the early rabbinic sources. (This was a period many centuries before the scientific understanding of fermentation, and the resulting scientific and technological advances of today by which technically correct/flawless wine may be made just about anywhere on earth.) The important take-away of the Talmudic discourse, in this context, is that one’s enjoyment of the wine mattered to them.

Thus, we find in the Babylonian Talmud the following:

Said Rabbi Yehudah quoting Shmuel: These four cups must be well diluted. If he drank them undiluted, he has [still] fulfilled his obligation…Rava said, ‘He has fulfilled his obligation of ‘wine,’ but not that of ‘freedom’ (Pesachim 108b).

As Maimonides explains in his codification of this ruling,

These four cups [of wine] should be mixed with water so that drinking them will be pleasant, [the proper ratio of which] all depends on the wine and the preference of the person drinking.

In contemporary terms, this Talmudic teaching and Maimonidean gloss point unequivocally to giving some thought and care to wine selection.

Beyond just the four cups—or eight cups between the two seder meals celebrated in the Diaspora—Pesach generally entails a lot of entertaining, and so more than a little wine to lubricate the proceedings.

As I never tire of arguing, wine and food pairing is to a very great extent a personal and individual matter. There is no “perfect” pairing per se, though perfection in the moment is attainable.

The goal of pairing wine with food is balance; neither the food nor the wine should overpower each other, and each component should, by and large, softly complement the other. It really ought not to require too much thought. General rules of thumb — like lighter foods with lighter wines, richer foods with richer, full-bodied wines — can be useful, but should not be treated as absolute. Sometimes contrasts work brilliantly too.

In the highly unlikely event that you’ve somehow failed utterly and the wine and food really don’t play at all nicely together, even though each is good separately, then simply have a little water before each sip of wine.

The bottom line: if the food and company and wines are generally good, you probably won’t go too far wrong regardless of the combo. There is no bolt of lighting that will strike down a supposed wine-and-food-pairing faux pas, and no heavenly voice to proclaim jejune combinations. Try to relax and not give it too much thought.

The only wine rule I consider inviolable is this: do not run out of wine!

An easy approach, as I never tire of arguing, is to opt for Beaujolais. I would especially recommend any of the Cru Beaujolais exclusively imported by kosherwine.com, such as their Louis Blanc Beaujolais Morgon 2019, Louis Blanc Cote de Brouilly Beaujolais 2018, or their Louis Blanc Beaujolais Julienas 2020. These red wines are sheer joy and, typical to nearly all Beaujolais wines, represent a unique style of delicious, fruity, fresh, red wines that have the weight, structure, and balance of a white wine. Beaujolais is best served slightly chilled.

I very firmly believe that every well provisioned wine lover and meal-host should incorporate Beaujolais into their routine.

NOTE:

The links to specific wines are provided for ease of access and to help folks identify the wines, they need not be purchased specifically from kosherwine.com and I receive zero benefits from anybody doing so. Likewise, I am a firm believer in supporting local businesses. That said, the folks at kosherwine.com are also great people providing a great service to kosher consumers farther afield.

Filling Your Four Cups

As for the four cups, really anything kosher and tasty will do. Still, for those seeking more definite guidance. Here are some suggestions to fill, and fulfill the mitzvah of, your four cups of kosher wine at the Pesach seder.

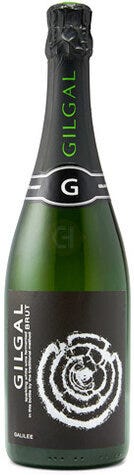

First Cup: Gilgal Brut (non-vintage)

I usually like to start the seder on a light but grand, pleasurable, and festive note. So, for kiddush I recommend a bubbly—indeed, given my druthers, I always prefer that the first kiddush of every festival be a bubbly. One of my favorites, and always very reasonably priced, is the non-vintage Gigal Brut from the Golan Heights Winery in Israel. Made in the traditional French Champagne method from Chardonnay and Pinot Noir grapes grown in Israel’s Galilee region, this is always lovely, bubbly, dry, crisp, and balanced.

Another fine option is the non-vintage Elvi Cava Brut from ElviWines in Spain. Also made in the traditional French Champagne method, the Elvi Cava is a blend of the Spanish grapes Perellada, Macabeo, and Xarello, and it too is lovely, dry, and elegant with wonderfully tight bubbles to keep it all very lively.

Other fine options to consider are: the Herzog Special Reserve Method Champenoise Chardonnay (non-vintagr), the Barons de Rothschild Brut Champagne Rosé (kosher edition; non-vintage), or the Hagafen Brut Cuvée 2017. There are many others too. Budget sparklers include: the Ma Maison Champagne Rosé, and, of course such popular lightly sparkling options like the Bartenura Moscato d’Asti and the Bartenura Malvasia.

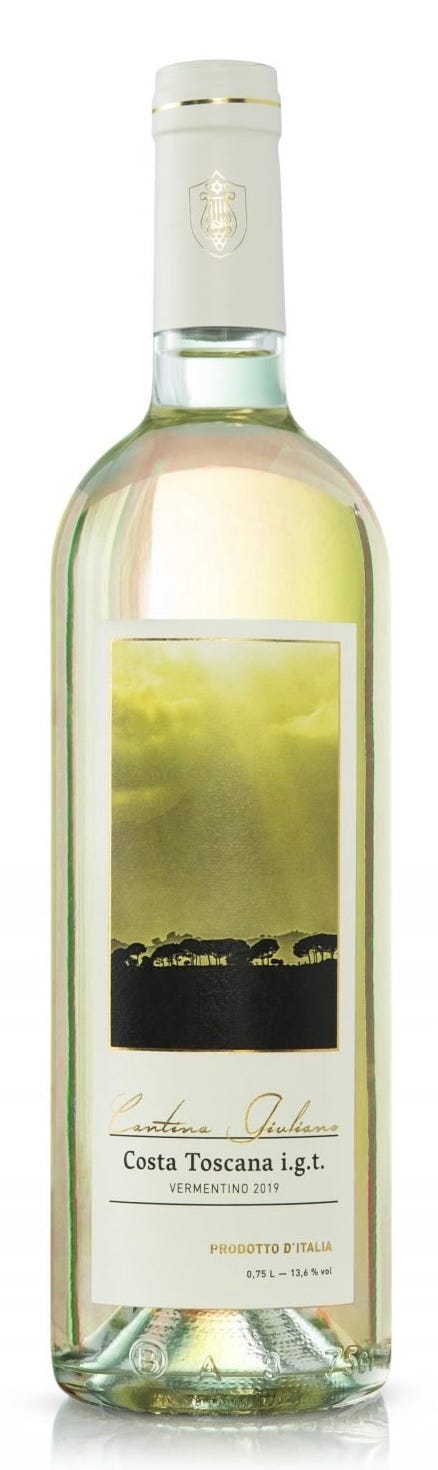

Second Cup: Cantina Giuliano, Vermentino, Costa Toscano i.g.t., Tuscany, 2020

The second cup should be not only tasty and of high quality, but to my mind should also serve as an aperitivo to stimulate appetites for the meal. This fabulous Tuscan Vermentino is typically crisp, refreshing and lovely, with a nose of honeysuckle, white pepper, apricot, citrus, almonds and gooseberry, and flavors of white peach, underripe apricot, citrus, guava and perhaps a little underripe pineapple. With palate-tingling acidity and enticing minerality, it hankers for good food.

Another very fine option would be the Les Marronniers Chablis Premier Cru 2018 (the 2020 was just released, but is not yet as widely available). This is a wonderful, crisp, flinty, restrained and elegant Chablis (an unoaked chardonnay from the Chablis region of Burgundy), with a fabulous, almost saline foundation upon which its restrained fruit notes dance about. Indeed, any of the currently available Chablis from Dampt Freres, or the La Chablisienne Chablis Cuvee Casher Premier Cru 2018 (a LiquidKosher.com exclusive) should also do very nicely.

Another interesting option, available directly from the Herzog Wine Cellars in CA, is the Herzog Limited Edition Acacia Sauvignon Blanc, Lake County, 2020. This is a lovely Sauvignon Blanc made using Acacia wood barrels rather than oak. The fruit shines here, more like a stainless steel Sauv Blanc than an oaked one, and you get the full aromatics — the moment it is poured the perfume presents a full array of passion fruit, lime, Granny Smith apples, gooseberry, and underripe peach; the aromas followed through to the palate. The acacia seems to have lent a little more texture and weight, perhaps a slight waxiness. Very tasty; beautiful finish.

Third Cup: ElviWines Herenza Rioja Crianza 2017.

For the third cup that accompanies Birkat Hamazon at the end of the meal, I seek refreshment, pleasure, and flavor—something that will nicely complement the feast I’m concluding and add agreeably to the happy flavors of the night. The Elvi Rioja Crianza now has some bottle age on it, offering elegant Rioja character, with beautiful and bright dark and red fruit notes, vanilla, black pepper, and some very agreeable earthiness, while keeping it all nicely refreshing.

Two other interesting options would be the Herzog Lineage Malbec 2019, and the Herzog Variations Be-Leaf Cabernet Sauvignon Organic 2020. The Malbec is fairly light but charming, with blue and dark red fruits, a slightly tannic texture, a nice kiss of black pepper, and a yummy lip-smacking finish. In contrast the Be-Leaf Cab is more of a heady ‘natural’ wine with no added sulfites, and already showing a little bit of tertiary bottle-aged character; slightly chunky tannins, fresh red and black fruits, decent acidity, and overall coheres nicely, with some finesse through the finish.

Fourth Cup: Golan Heights Winery, Yarden, Heights Wine, 2018 (375ml):

To accompany Hallel, I generally want a cup that is tasty and satisfying, and also a wine that will very happily add to the mental buzz of happy flavors and thoughts from the evening’s program. There are a great many options that work here, but I figured ending the seder on an Israeli note seemed apropos. Made from Gewürztraminer grapes that have been artificially frozen in the winery after harvest, this is, as always, delicious, rich, and aromatic with notes of lychee, apricot, peach, citrus, and spice, with great balancing acidity and a rewarding, complex finish. Very yummy.

L’chaim!

About me:

By way of background, I have been drinking, writing, consulting, and speaking professionally about kosher wines and spirits for more than 20 years. For over a dozen years I wrote a weekly column on kosher wines and spirits that appeared in several Jewish publications, and my writing generally has appeared in a wide variety of both Jewish and non-Jewish print and online media. A frequent public speaker, I regularly lead tutored tastings and conduct wine and spirits education and appreciation programs. Those interested in contacting me for articles or events can do so at jlondon75@gmail.com.

In what seems like a lifetime ago, I also wrote an entirely unrelated slice of American history: Victory in Tripoli: How America’s War with the Barbary Pirates Established the U.S. Navy and Shaped a Nation (John Wiley & Sons, 2005).

These days I divide my time between London (UK), and Washington, DC.